Many people assume that using a VPN is enough to keep their browsing private. It's true that VPNs hide your IP address and shield your traffic from your ISP (which is why they're often recommended for activities like torrenting). But there's another powerful tracking technique that a VPN cannot stop: browser fingerprinting.

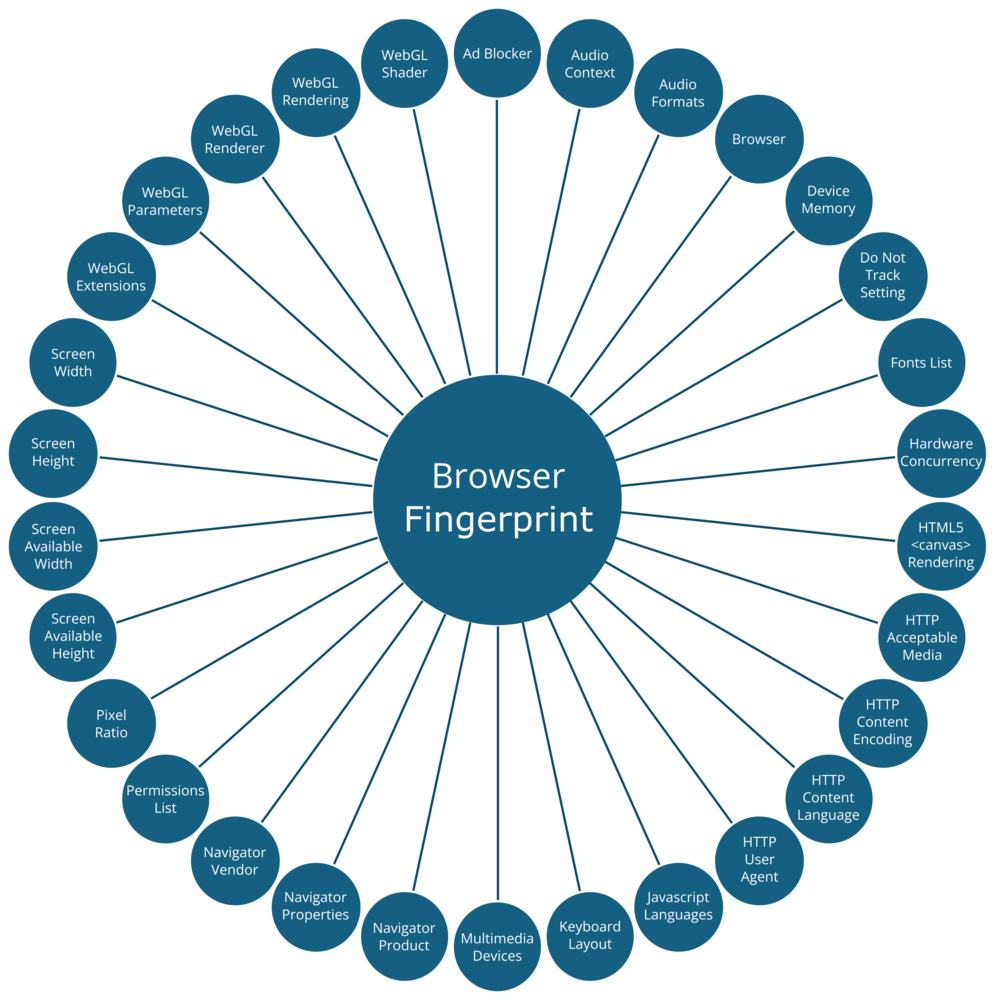

When you visit a website, your browser reveals a staggering amount of information about your device. Details like your browser version, language settings, screen resolution, installed fonts, and even available memory are all exposed, regardless of VPN use. On their own, each piece of data seems harmless. But taken together, they form a unique "fingerprint" of your device that allows websites to identify you.

This kind of identification isn't inherently bad. Banks, for example, may use it to verify logins from new devices and trigger additional security checks. But the same technique can also be used for less welcome purposes, such as ad networks tracking your browsing habits across the web. And unlike cookies, you can't simply opt out of this type of tracking. It's also worth noting that private or 'incognito' browsing modes don't prevent fingerprinting. These modes are designed mainly to hide your browsing history from other users on your device, not from websites collecting data about your system.

At RTINGS.com, we take privacy seriously. A few years ago, we switched to a privacy-friendly analytics tool (Plausible), even though it meant having less information about our visitors. More recently, as we've experimented with ads on the site, we've remained mindful of the trade-off: while we don't collect more identifying information ourselves, the ad stack may gather data depending on what visitors select in the consent management platform.

This ongoing balancing act prompted us to test browser fingerprinting across our team of 83 colleagues. Despite using a small set of nearly identical Windows laptops, every single one of us had a unique browser fingerprint. In other words, even if our IPs were hidden behind a VPN, websites could still tell us apart.

That's why VPNs are best thought of as necessary, but not sufficient for online privacy. To make yourself less trackable, you need to understand how fingerprinting works and take steps to reduce your uniqueness.

In this article, you'll learn why a VPN alone won't keep you anonymous, how you can reduce the uniqueness of your fingerprint, and what our experiments across 83 laptops reveal about just how powerful this tracking technique really is.

Why A VPN Alone Cannot Help

If you browse without a VPN, your IP address is fully exposed, which by itself can make your system uniquely identifiable. Using a VPN is therefore an important first step for protecting your privacy: it masks your IP and shields your activity from your ISP. However, a VPN alone is not enough. Most core browser fingerprinting techniques do not rely on IP addresses, which means that even with a VPN active, your device can still be uniquely identified.

To demonstrate this, we collected fingerprint data using amiunique.org, a service developed by the French National Institute for Research in Digital Science and Technology. These were collected from the same Windows PC while connected through four different VPNs (all set to U.S. West Coast servers) and once without any VPN:

In every case, the fingerprint we hashed from the collected data remained completely unchanged.

| System State | Reported IP Address | Reported Timezone Code | Fingerprint Hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| No VPN | 184.163.***.*** | +240 | 13f0e5a28087ab561ac6d89442f979ea |

| Mullvad | 146.70.173.107 | +240 | 13f0e5a28087ab561ac6d89442f979ea |

| NordVPN | 181.215.169.218 | +240 | 13f0e5a28087ab561ac6d89442f979ea |

| Proton | 146.70.174.86 | +240 | 13f0e5a28087ab561ac6d89442f979ea |

| TunnelBear Free | 98.98.100.212 | +240 | 13f0e5a28087ab561ac6d89442f979ea |

One noteworthy observation was the timezone code. Even when connected through a VPN endpoint on the U.S. West Coast, the fingerprint still reported our local Eastern North American timezone offset of +240 minutes. This happens because the timezone captured during fingerprinting reflects the system clock, not the IP address.

This discrepancy between system timezone and VPN endpoint location can actually make VPN usage more detectable. While a VPN can successfully conceal your IP address, it does nothing to hide the much richer set of attributes exposed by browser fingerprinting.

How To Make Your Fingerprint Less Unique

If VPNs are only a first step, what else can you do to protect your privacy? The challenge with browser fingerprinting is that it collects far more than just your IP address. Websites can learn details about your device and browser settings that, when combined, make you stand out. You can't completely avoid this because this exchange of information is how the modern web is built, but you can make your fingerprint less unique and therefore harder to track.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches:

- Standardize your fingerprint so it looks the same as many others.

- Randomize your fingerprint so it looks different every time.

There isn't a single best option. As is often the case with privacy protection, it ultimately comes down to striking the right balance for your own privacy needs and tolerance for inconvenience.

Standardizing Your Browser Fingerprint

One way to reduce uniqueness is to standardize your fingerprint so it looks the same as many others. Some privacy-focused browsers, like the Tor Browser and the Mullvad Browser, purport to do exactly this. They attempt to limit the amount of information websites can collect by forcing standardized values, a strategy that can make it much harder to single you out.

To see how this works in practice, we compared fingerprints collected by amiunique.org from Chrome, Mullvad, and Tor running on the same laptop. Even at a glance, you can see how Tor strips away or spoofs many of the attributes that make Chrome look unique:

What this table shows is the potential power of standardization. Chrome reveals your real setup in detail, while Mullvad and Tor force most users to appear the same. For example, your browser window is letterboxed into fixed sizes, your languages are generic, and WebGL rendering is blocked.

There are trade-offs, however. Using a less common browser like Tor or Mullvad may itself make you stand out if adoption is low. And while default settings allow JavaScript (which most websites need), enabling Tor's highest "Safest" mode blocks JavaScript altogether, giving you stronger privacy at the cost of breaking many modern websites.

Randomizing Your Browser Fingerprint

Another strategy is to randomize your browser fingerprint so it looks different every time you visit a site. The idea is that if your attributes keep changing, it becomes much harder to link your browsing sessions together.

The Brave Browser takes this approach by default. Instead of making every user look the same, it shuffles certain identifying attributes for each session. To see this in action, we collected fingerprints from amiunique.org across two Brave sessions on the same machine.

| Attribute | Brave Browser Session 1 | Brave Browser Session 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Languages | en-GB,en;q=0.5 | en-GB,en;q=0.7 |

| HTML5 Canvas Fingerprint Hash | bb3ec7bfca2048ad8f1a265cba006ef4 | 5c383c209ef917acc4ef66ea45036bad |

| WebGL Rendering Hash | 9970926e8379d5ae65787bb88c745656 | 928d63d21e9c8c4c3d7320647e6094fd |

| WebGL Render Buffer Size | 8876 | 8871 |

| Browser Viewport Height | 1687 | 1639 |

| Window Outer Height | 591 | 594 |

| Window x-Position | 3 | 2 |

| Device Memory | 0.5 | 2 |

| Additional Fonts | Pristina | Monotype Corsiva |

| Hardware Concurrency | 4 | 8 |

| Plugins | Plugin 0: PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 1: Microsoft Edge PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 2: 4cOmyCJ; 2EhvfuAn6dt9e2bNl5k5k5kxBIr0iZU; d1iZMOPufu26GDJ. Plugin 3: Chromium PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 4: WebKit built-in PDF; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 5: DJEKFhvf; hvf2j4FCo7GDJEKFpc1iZUxgvXToUKkS; bVKkaNlx3bNtePPm. Plugin 6: Chromium PDF Display; Portable Document Format; ylaVSJjZMOHLs9mTRIECgYz4k5k5kxBI. | Plugin 0: Browser document Plugin; Portable Document Format; ujwYMOHLs9mb057laNlx3j4FCgYrVxg3. Plugin 1: Microsoft Edge PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 2: bsWyhQI; 4FCgQQvAny4kxBIjZUxYUxYMOHDBnyC; FOHLs9mTRIMtePH. Plugin 3: OLFpUKs1; 0iZUp7GLs9e2bVSJr899HqVp7GLs1Do7; Pq0iZUxgvfu2Eh36. Plugin 4: PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 5: WebKit built-in PDF; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. Plugin 6: Chromium PDF Viewer; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer. |

These results show how Brave alters key attributes from one session to the next. The canvas fingerprint, WebGL rendering details, and installed fonts all shifted between visits, making it theoretically harder for a website to reliably link the two sessions to the same user.

As with standardization, there are trade-offs. Brave is a less common browser than Chrome or Firefox, which means simply using it may already make you stand out. And in its default mode, Brave's randomization is seeded with your true values. Therefore, while the reported attributes look different from session to session, the underlying originals could still be inferred. Switching to “Maximum” security avoids this by fully randomizing the attributes, but that stronger protection comes at the cost of breaking many websites.

Our Recommendations

Ultimately, digital privacy is always about trade-offs: how much risk you're willing to accept, how much usability you're prepared to give up, and what level of peace of mind you want. There's no single "best" approach, only the balance that works for you. Generally, we suggest using a VPN alongside a privacy-oriented browser (such as Brave, Mullvad, or Tor). You can see our up-to-date list of recommended VPNs here.

If you're extremely privacy-conscious, Tor Browser on the 'Safest' settings may offer the strongest protection, but at the steep cost of breaking many websites. Also, stay mindful that using a VPN along with Tor Browser can break the anonymity provided by the Tor Network if misconfigured. To learn more about how to set it up correctly, we recommend this guide from PrivacyGuides.org. For most people, Brave in its default mode strikes a more practical balance. However, it's worth remembering that Brave's smaller user base may itself make you stand out and that its default randomization is still seeded by your true values.

Another effective strategy is to use more than one browser. For example, you might rely on Mullvad or Tor for everyday browsing where you aren't logging into any website. In this case, you're just a person, part of the masses browsing the web without much personal info attached to you. Use a second browser like Brave or Firefox (with appropriate security settings) to log into your accounts or access trusted websites where you don't mind being identified. Splitting your browsing this way reduces the amount of data any single browser reveals and minimizes data associated with your accounts, giving most users a reasonable balance between privacy and usability.

Fingerprinting Our Colleagues' Browsers

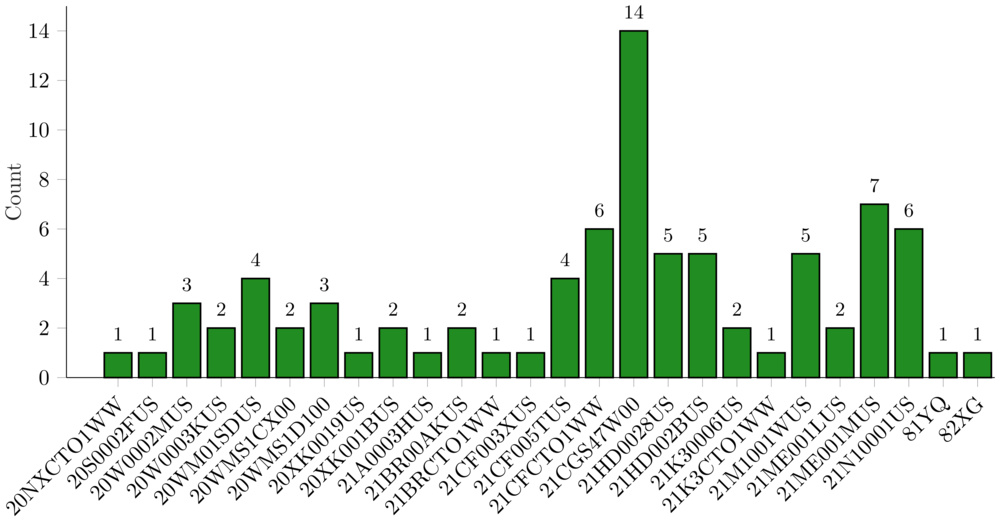

Given how powerful browser fingerprinting can be, we wanted to see just how identifiable we might be when going online using the same small set of Windows work laptops. At RTINGS.com, our laptops are purchased in batches with identical specifications as the company has grown. This means we have anywhere from a single unit of a particular model to more than a dozen of the same model, as illustrated in the histogram below:

For our experiment, each colleague collected information about their laptop and its browser fingerprint. To keep conditions consistent, we asked everyone to unplug peripherals such as external monitors, keyboards, or mice. System-level information was exported directly from Microsoft Windows "System Information."

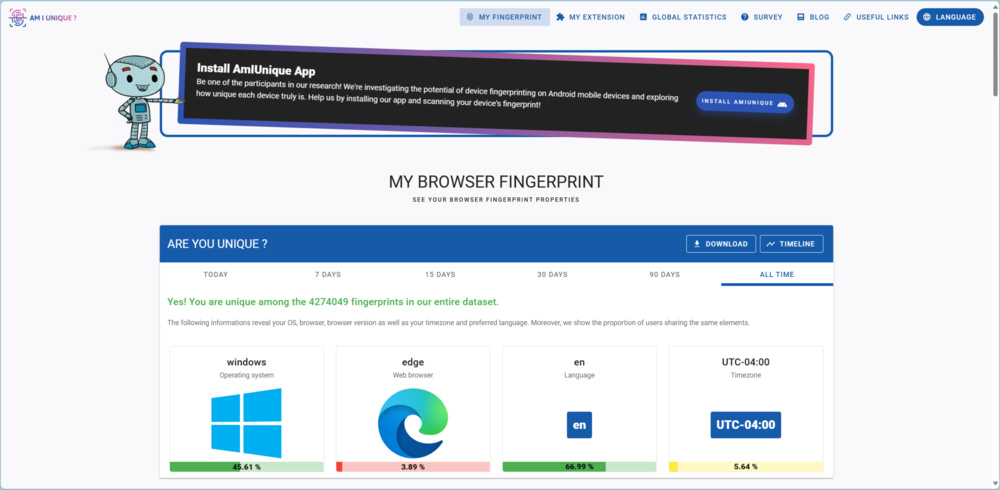

To capture the kind of data a website can actually observe, participants visited amiunique.org. Each person used their everyday web browser, ensuring the results reflected a realistic, real-world browsing environment.

Once collected, the data was collated and analyzed using Python scripts. For fingerprint attributes that contained multiple values (such as lists of installed fonts or browser permissions), we standardized them by creating ordered, concatenated strings and hashing the result. This gave us single, comparable values for analysis.

The Web Operates On Exchanging A Lot Of Information

Our first surprise came when we looked at the raw data collected from our colleagues. Simply by visiting a single website, each laptop revealed an enormous amount of information. The structured data files returned by amiunique.org contained nearly 1,500 individual system properties per device.

The challenge for personal privacy is that much of this information is exchanged as part of the normal functioning of the web itself. For example, whenever you load a webpage, your browser automatically sends HTTP headers to the server. These headers include the details listed in the following table:

| HTTP Header Information Exchanged | |

|---|---|

|

Operating System Supported Encoding |

Browser Version Acceptable Media Installed Languages |

In addition, websites can use JavaScript to request more details about your system. While most JavaScript simply powers normal site features like menus, animations, or interactive buttons, it can also be written to probe attributes of your device for fingerprinting purposes. Because JavaScript is so deeply embedded in the modern web, disabling it for privacy would also disable much of the functionality that makes websites usable. In many cases, it would prevent sites from loading altogether.

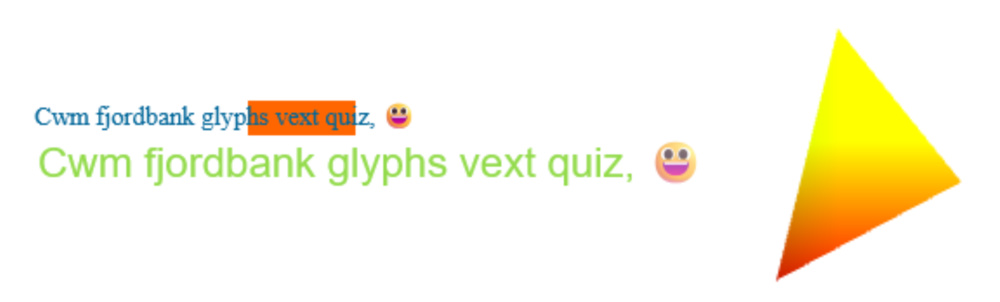

JavaScript also enables one of the more striking identification techniques: canvas fingerprinting. Here, your browser is asked to render an image using the HTML5 <canvas> element and WebGL. The resulting output isn’t identical across systems; it depends on the exact combination of OS, GPU, drivers, browser, and even installed fonts. This subtle variability makes the canvas fingerprint highly distinctive, often unique.

| Javascript Information Exchanged | |

|---|---|

|

Enabling of Cookies Installed Languages Installed Fonts Do Not Track Setting Browser Version Device Memory Screen Resolution WebGL Renderer + Parameters Media Input Devices Keyboard Layout |

Timezone Canvas Fingerprints Use of Ad Blocker Web Navigator Properties Hardware Concurrency Installed Browser Plugins Browser Permissions Acceptable Media Formats System Sensors System Taskbar Layout |

Every One Of Our Colleagues Had A Unique Browser Fingerprint

When we first checked our results on amiunique.org, the site reported that every one of our colleagues had a unique fingerprint, even compared against the more than 4 million devices in their database. Impressive as that sounds, their definition of “uniqueness” is a little misleading. The hashes they generate include connection-level details such as IP addresses and battery charge state information. Since IP addresses can be easily hidden behind a VPN and battery information is constantly changing, they fall outside the scope of what’s typically considered core browser fingerprinting.

To get a clearer picture, we dug into the raw data collected and created our own set of fingerprint hashes. We restricted the attributes used in these hashes to 28 fields, deliberately removing those that didn't meaningfully differentiate devices in our dataset. For example:

- Browser plugins are largely deprecated, and Chrome, Edge, and Firefox all reported only the same built-in PDF viewers (with Brave returning a randomized string).

- Every participant had cookies enabled.

- None of the laptops reported an accelerometer or proximity sensor.

- All systems were running Windows.

Even after narrowing the scope, the results were striking: 83 out of 83 colleagues had a unique browser fingerprint hash. Admittedly, with a relatively small dataset and a fairly large set of attributes, uniqueness is easier to achieve. But the finding is still noteworthy given that so many of us were using nearly identical hardware.

We Didn't Need A Long List Of Attributes To Uniquely Identify Our Colleagues

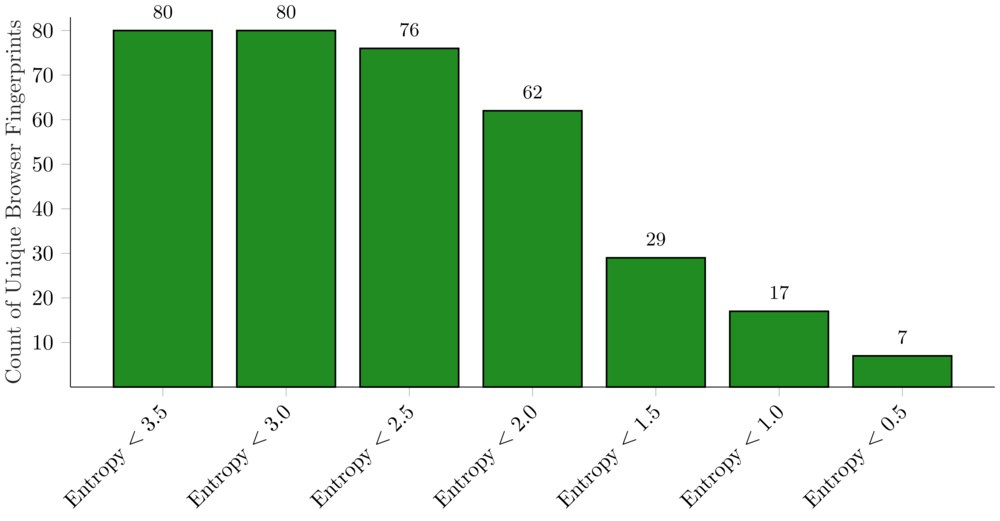

To better understand which attributes contribute most to our identifiability online, we analyzed the results using Shannon entropy (H) for each fingerprint attribute:

where the pᵢ is the probability of the ith outcome:

Entropy measures the amount of uncertainty, or unpredictability, in a dataset. Attributes with low entropy are highly predictable, with few unique values, making them less useful for distinguishing individuals. Attributes with high entropy, by contrast, are unpredictable with many unique values, making them far more powerful for identification.

When sorted by Shannon entropy, the browser fingerprint attributes in our dataset ranked as follows:

| Attribute | Unique Value Count | Shannon Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP Content Encoding | 1 | 0.00 |

| WebGL Shader | 2 | 0.16 |

| Audio Context | 3 | 0.39 |

| Do Not Track Setting | 2 | 0.56 |

| Navigator Product | 2 | 0.65 |

| Navigator Vendor | 2 | 0.65 |

| Device Memory | 3 | 0.75 |

| Multimedia Devices | 3 | 0.75 |

| HTTP Acceptable Media | 3 | 0.81 |

| WebGL Extensions | 3 | 0.81 |

| Permissions List | 4 | 0.90 |

| Ad Blocker | 2 | 0.94 |

| WebGL Parameters | 8 | 1.27 |

| Keyboard Layout | 4 | 1.29 |

| Navigator Properties | 6 | 1.31 |

| Audio Formats | 4 | 1.49 |

| Browser | 4 | 1.56 |

| Hardware Concurrency | 6 | 1.71 |

| Pixel Ratio | 7 | 1.87 |

| HTTP User Agent | 9 | 2.42 |

| Javascript Languages | 17 | 2.42 |

| Screen Width | 12 | 2.69 |

| Screen Available Width | 12 | 2.69 |

| HTTP Content Language | 16 | 2.77 |

| Fonts List | 20 | 2.90 |

| Screen Height | 15 | 3.37 |

| WebGL Renderer | 20 | 3.60 |

| Screen Available Height | 19 | 3.63 |

| WebGL Rendering | 21 | 3.73 |

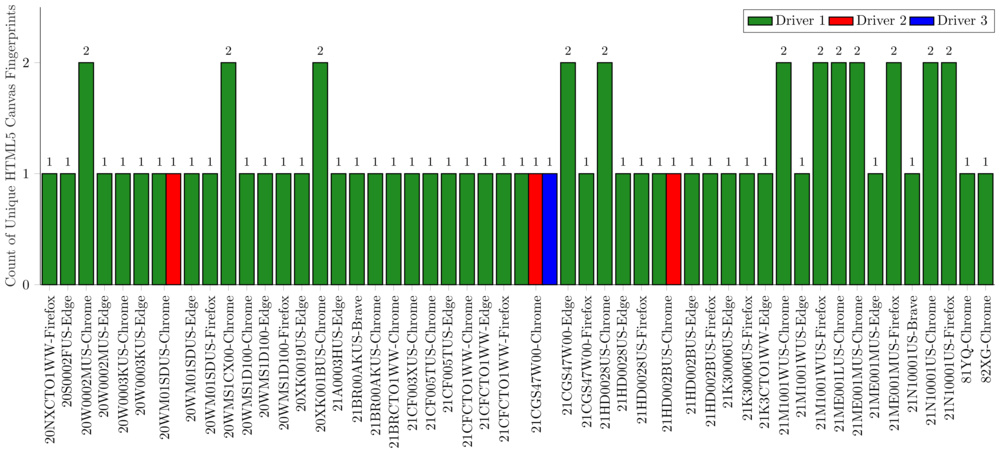

| HTML5 Canvas Rendering | 31 | 3.81 |

Unsurprisingly, the attributes with the highest entropy were the HTML5 canvas and WebGL rendering fingerprints. Across our group, the HTML5 element produced 31 distinct renderings, while WebGL produced 21 distinct renderings. When grouped by laptop model, browser, and graphics driver, there were at most two fingerprints per combination. This shows just how tightly these rendering fingerprints are linked to the underlying hardware and software, making them highly effective identifiers. However, they are not perfectly stable: changes to graphics drivers or browser versions can alter the fingerprint over time.

Another notable finding was the large number of unique screen resolution combinations. Resolution is affected both by a laptop's native display size and by user-set pixel scaling in Windows. "Available resolution" values varied depending on the size of the taskbar set by the user, further increasing uniqueness.

We also found 20 distinct font combinations and 17 distinct language configurations. As a bilingual French-English workplace, this was expected. Though interestingly, we observed multiple regional variants (e.g., Canadian vs. American English, and Canadian vs. metropolitan French).

To test the necessity of individual attributes, we recreated the fingerprint hashes while removing one attribute at a time. In every case, all fingerprints remained unique meaning no single attribute was solely responsible for uniqueness.

Next, we wanted to see how much entropy could be removed before uniqueness broke down. We successively removed attributes with the highest entropy and tracked the number of unique fingerprints remaining. Even after discarding all attributes with entropy greater than 2.0, we could still uniquely identify 62 out of 83 colleagues.

The table below lists the attributes with entropy less than 2. Note how few unique values each contains. This highlights the core insight: it is not any single attribute that makes a browser fingerprint unique, but rather the intersection of many otherwise mundane attributes.

| Fingerprint Attribute | Unique Value Count | Shannon Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP Content Encoding | 1 | 0.00 |

| WebGL Shader | 2 | 0.16 |

| Audio Context | 3 | 0.39 |

| Do Not Track Setting | 2 | 0.56 |

| Navigator Product | 2 | 0.65 |

| Navigator Vendor | 2 | 0.65 |

| Device Memory | 3 | 0.75 |

| Multimedia Devices | 3 | 0.75 |

| HTTP Acceptable Media | 3 | 0.81 |

| WebGL Extensions | 3 | 0.81 |

| Permissions List | 4 | 0.90 |

| Ad Blocker | 2 | 0.94 |

| WebGL Parameters | 8 | 1.27 |

| Keyboard Layout | 4 | 1.29 |

| Navigator Properties | 6 | 1.31 |

| Audio Formats | 4 | 1.49 |

| Browser | 4 | 1.56 |

| Hardware Concurrency | 6 | 1.71 |

| Pixel Ratio | 7 | 1.87 |

Using Only "Stable" Attributes Still Allows For Identification

As noted earlier, some attributes, like the HTML5 canvas and WebGL rendering fingerprints, have very high Shannon entropy and therefore strong identification power. However, they are also relatively unstable since they can change whenever graphics drivers or browsers are updated.

To focus on attributes that better reflect the long-term identity of a system, we narrowed the list down to those that are not expected to change frequently:

- Physical system attributes (e.g., screen resolution, memory)

- OS-level settings that are usually configured once and rarely altered (e.g., pixel ratio, language packs, keyboard layout)

| Fingerprint Attribute | Unique Value Count | Shannon Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP Content Encoding | 1 | 0.00 |

| Device Memory | 3 | 0.75 |

| HTTP Acceptable Media | 3 | 0.81 |

| Keyboard Layout | 4 | 1.29 |

| Browser | 4 | 1.56 |

| Pixel Ratio | 7 | 1.87 |

| Javascript Languages | 17 | 2.42 |

| Screen Width | 12 | 2.69 |

| Screen Available Width | 12 | 2.69 |

| HTTP Content Language | 16 | 2.77 |

| Fonts List | 20 | 2.90 |

| Screen Height | 15 | 3.37 |

| Screen Available Height | 19 | 3.63 |

Even with this much shorter list of stable attributes, we were still able to uniquely identify 68 out of 83 devices in our dataset. This highlights how persistent uniqueness can be, even without relying on more volatile attributes.

Conclusion

Our small experiment highlights just how much identifying information your browser reveals whenever you visit a website. Browser fingerprinting is not inherently good or bad; it can enable important security checks, but it can also be used for invasive tracking. The reality is that simply running a "stock" browser to blend in or relying on a VPN alone won't make you anonymous. Fingerprinting works by combining a wide range of attributes, far beyond just your browser settings or IP address.

Instead, protecting your privacy online means choosing the right balance of tools for your needs. To reduce your uniqueness, you may need to consider browsers that standardize or randomize fingerprints, or even split your activity across multiple browsers. Absolute anonymity is unrealistic, but with the right strategies, you can make tracking harder and keep your browsing more private.