The throbbing thump of a subwoofer at your favourite club, or the feeling of zoning out on your bed with your headphones cranked up; if you're reading this, you're probably well-aware of just how thrilling immersing your ears (and body) in sound can feel (sound baths are a phenomenon for a reason). But, there's a fine line between immersion and "uh-oh, my ears are still ringing". Push past it too often, and you can permanently damage your hearing. In this article, we'll unpack what loudness is and how it differs from things like volume. We'll discuss decibels and other ways of measuring loudness, and then give you some guidelines for safe listening levels and share practical tips to protect your ears while still enjoying the music.

What Is Loudness?

We can't explain everything there is to know about the complex phenomenon of loudness. Most of you are probably here because you just want to know how loud is too loud for headphones and speakers! And we've got you covered. But to avoid turning your playlists into a one-way ticket to tinnitus, it helps to know what 'loud' actually means, how we measure it, and where the safe zone ends.

Don't Get Your Terms Crossed: Making Sense Of Loudness, Level, Amplitude, And Volume

In scientific terms, loudness is the subjective perception of sound pressure by the human ear. It's a psychoacoustic phenomenon, involving not just the level of the physical sound waves themselves, but how we perceive them. In that regard, loudness is slightly different from sound level, although the words are sometimes used interchangeably. And what of volume? Volume's a rather slippery word. In an audio context, people use it to mean everything from perceived loudness to sound level to those little knobs or sliders on your audio playback device. For our purposes, we like to think of volume as being tied to the level change mechanism, since level and loudness have more specific meanings within the audio field.

Amplitude is the size of a sound wave's vibration, while frequency is how fast the wave vibrates per second, measured in hertz (Hz). The lowest string on a bass guitar vibrates at 41.2Hz, while the highest string on a regular guitar vibrates at 329.6 Hz. This matters because our ears don't perceive all frequencies equally, as we'll explain shortly.

To sum it up: turning up the volume control on your stereo increases the sound level (the amplitude of the sound waves), which also increases the perceived loudness. But how much louder your audio sounds depends on many factors, including your hearing sensitivity, the sound's characteristics (including its frequency), and the playback device. If your volume is maxed out and you still want more loudness, head over to our article on how to make your headphones louder.

You want to know how many decibels is too loud, but what even is a decibel? To quantify sound intensity in the real world, we use several closely related units that you'll run into often:

- Decibels (dB): The decibel is a relative unit of measurement used to express ratios of two values on a logarithmic scale. It's often used in electronics or signal processing to express gain, attenuation, or dynamic range. In audio signal processing, a 6 dB increase means the output power is roughly twice the input power. For example, if your headphone pre-amp doubles the input voltage at its output stage, you can expect a roughly 6 dB louder signal.

- Sound Pressure Level (SPL): The physical measure of sound pressure, expressed in decibels. It's a way to quantify how strong a sound wave actually is. The scale is referenced such that 0 dB SPL corresponds to the approximate low threshold of human hearing (about 20 µPa of pressure). Typically, speaking voices hover around 60 dB SPL at a close distance, while a loud rock concert might easily exceed 100 dB SPL.

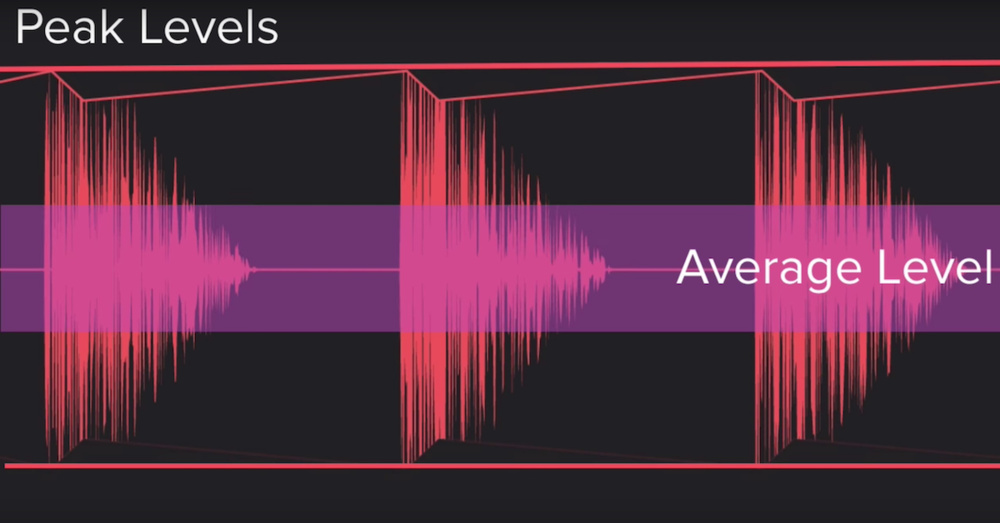

- Peak Volume: The instantaneous maximum level of a sound. It tells you how something is at its loudest moment. Peak readings capture these momentary spikes.

- RMS (Root Mean Square): This is, more or less, the average power level of an audio signal over a short time window (typically around 300ms). RMS smooths out the peaks of a sound and correlates better with how we perceive loudness for sustained sounds.

- dBFS (Full Scale): Is the unit used to measure the amplitude of a digital audio signal. 0 dBFS is the maximum possible level in a digital system: if you go above this, your audio clips. (Clipping isn't very noticeable if it happens rarely or only by a small amount, but large amounts sound like harsh digital distortion.) As a result, digital audio signals are measured in negative dB values, like -3 dB. Professionally-mastered music tends to peak between -1 and 0 dBFS. And again, since these are still decibels, -6 dBFS is 50% of the maximum possible output level of the digital system.

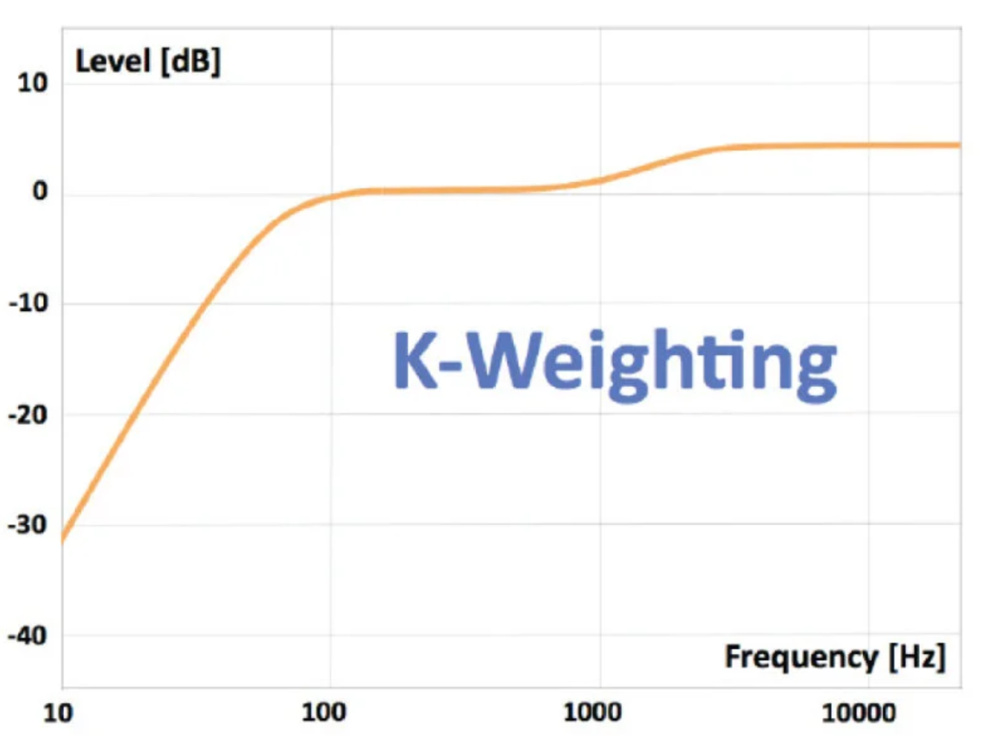

- LUFS (Loudness Units relative to Full Scale): This is a standardized way of measuring perceived loudness over time in digital audio, taking into account how humans hear different frequencies. Unlike the peak-based dBFS, LUFS reflects how loud something actually sounds to us, not just how high the levels spike. There are two main LUFS types: Integrated LUFS measures average loudness over an entire track, while Momentary and Short-Term LUFS capture changes over brief time windows, kind of how RMS measurements work. Professionally-mastered contemporary popular music tends to have an integrated LUFS value of between -5 and -13 LUFS, with 1 LU corresponding to a 1 dB change in level.

Loudness Curves

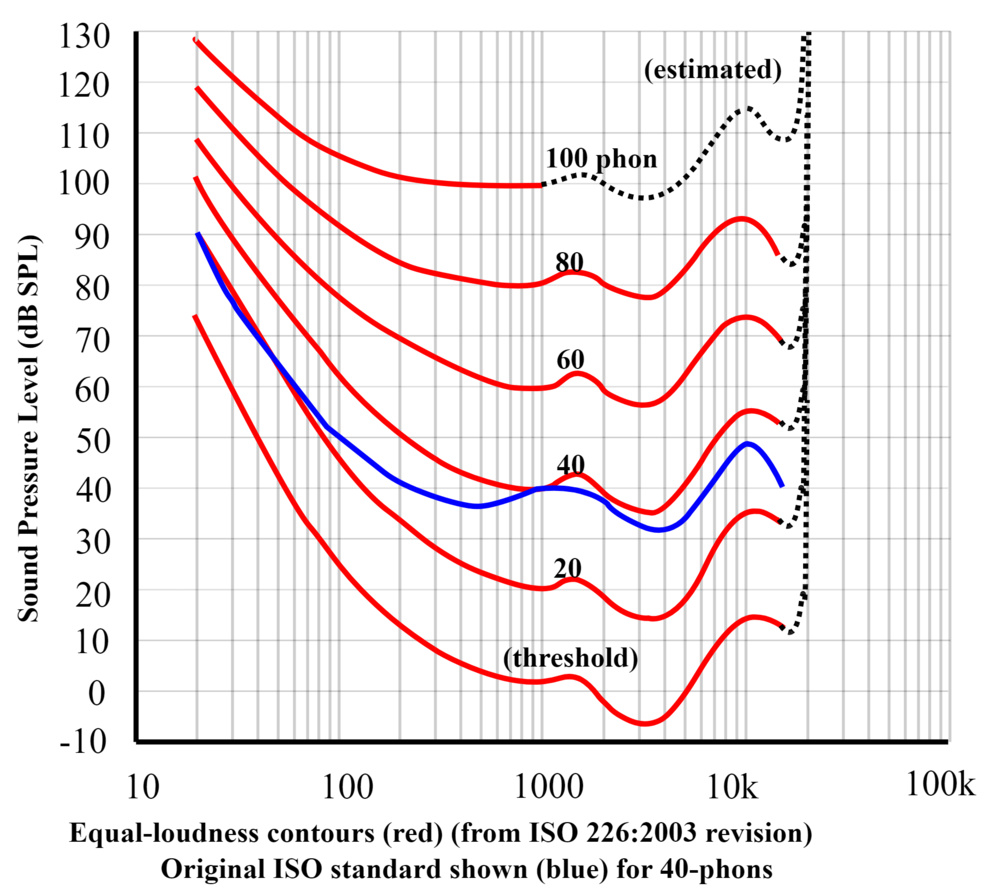

Loudness weighting accounts for the fact that our ears don't hear all frequencies equally well. We're most sensitive to sounds in the 2–5kHz range, where much of the character of human speech resides. We're less sensitive to very low or very high frequencies. This was first measured in the 1930s by researchers Harvey Fletcher and Wilden A. Munson, who produced a series of curves showing how loud different frequencies need to be to sound equally loud to us. These Fletcher-Munson curves were the first equal-loudness contours. Modern versions of these curves show that a 50Hz bass tone might need to be 20–30 dB louder than a 1kHz tone to feel equally loud to us.

Weighting Filters

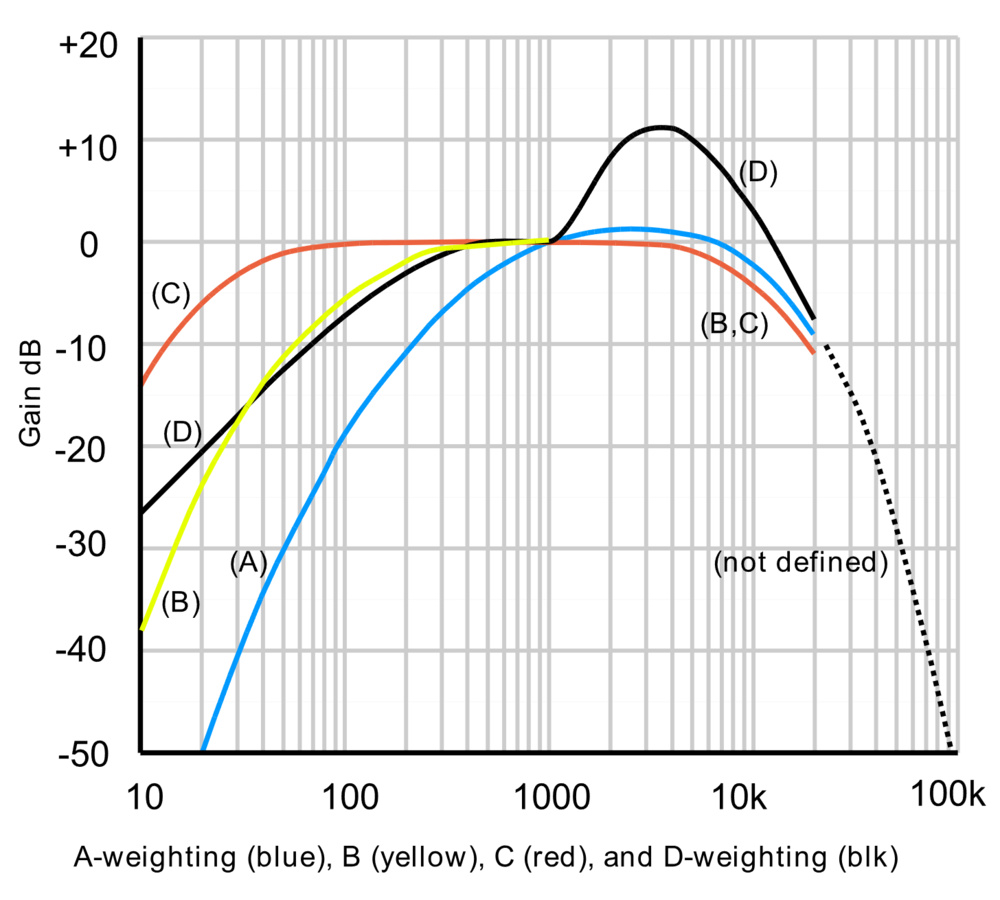

To reflect these contours, engineers can use weighting filters when measuring loudness, which adjust decibel readings to better match human perception. The most common is called A-weighting, which de-emphasizes bass and treble to simulate our ears' sensitivity at moderate listening levels. Sound levels measured this way are labeled dBA. There are also B-weighting and C-weighting systems, used for higher volume levels or broader frequency responses, but dBA is the most widely used for general sound exposure and headphone testing. LUFS meters use the K-weighting system.

The key point to bear in mind is that two sounds with the same raw dB SPL can have different dBA readings. For example, a deep bass note and a mid-range tone might both measure 80 dB unweighted, but the A-weighted meter will register the bass as quieter, because that's more in line with what we actually hear. This helps measurements correspond more closely to perceived loudness, and is why dBA is used in noise regulations and safe listening guidelines.

|

|

Short-Term Versus Long-Term Loudness

Our ears perceive a quick, sharp sound differently from a continuous one. A sudden transient (like a snare drum hit or firecracker) might spike at a very high volume momentarily, but because it's so brief, our immediate impression can be that it doesn't feel as loud as a lower-volume noise that persists, like a jackhammer outside your window. If the peak is extremely high (like a close-up gunshot or firecracker), it can cause instantaneous damage. In fact, exposure to noise peaks around 120 dB SPL or above, even for a split second, can cause immediate harm. One reason for this is that the human auditory system has a built-in protective mechanism (the acoustic reflex) that engages for loud continuous sounds. But this reflex has a slight delay, so it may not activate in time for an abrupt, split-second noise.

Still, most of us (drummers excepted) aren't listening to a series of short, sharp shocks all day. But we regularly listen to more sustained noise, whether in our headphones or standing near a speaker at a rock concert. In these cases, the sound level might be lower in peak dB than the snare hit, but it's relentless. After even a minute or two, your ears start to perceive the audio as very loud because there's no relief, while after an hour, you might notice your ears ringing. Sometimes, sustained noise can be more dangerous because you acclimate to it over time.

How Loud Is Too Loud?

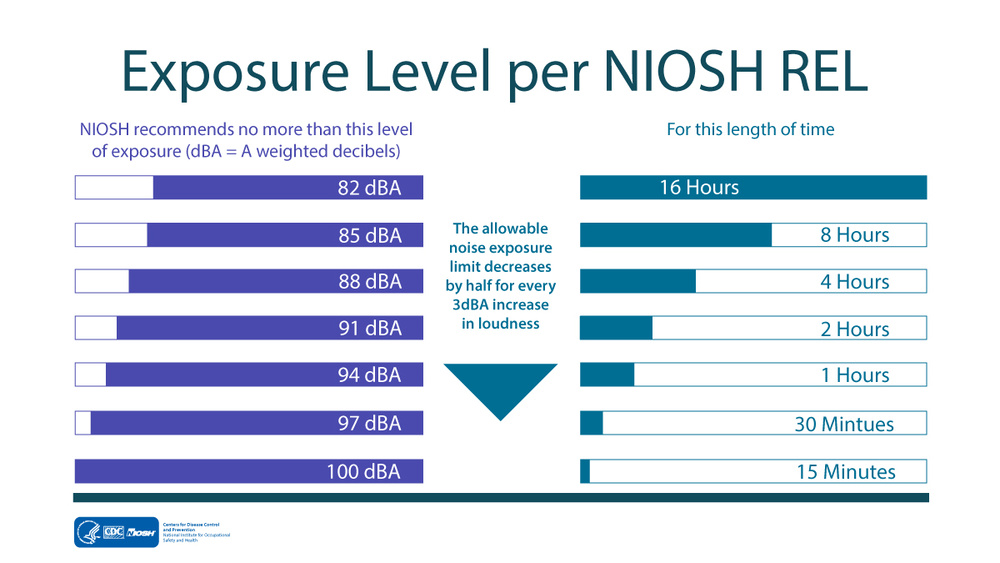

Alright, we've reached the meat of the article. If you just want one simple answer so you can get on with your life: 85 dB (A-weighted, which is the standard weighting used for loudness safety measurements) is considered a safe, sustained listening level for eight hours by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Eight hours is long enough to cover an average workday or a solid sleep. Stay beneath 85 dBA (or even 80 dbA, if you want to be safe) for the duration, and you'll likely be fine.

But, as always, the devil is in the details. Listening at 85 dBA for long periods isn't completely risk-free: prolonged listening at that level every day could still cause some damage over the long term, which is why experts emphasize not just loudness but also duration: safe listening also means giving your ears plenty of quiet time to recuperate each day.

How Safe Loudness Levels Vary With Listening Time

Safe listening guidelines are based on an 'exchange rate' where every 3 dB increase halves the safe exposure time (because decibels operate on a logarithmic scale, remember). That's why it's difficult to say how many decibels is too loud, because the figure changes depending on your exposure length. Here's a brief list of how safe listening durations vary with loudness:

- 60 dB SPL, A-weighted: About the level of a normal conversation; you could listen at this volume all day without risk.

- 70 dBA: Similar to a vacuum cleaner across the room; generally safe for up to 24 hours of exposure.

- 85 dBA: Comparable to heavy city traffic or a loud restaurant; the safe listening limit drops to about 8 hours.

- 88 dBA: Like a busy club or gas lawnmower; safe exposure time is reduced to about four hours.

- 94 dBA: Roughly the volume of a motorbike at close range; only safe for around one hour.

- 100 dBA: Similar to a rock concert or some gaming headsets at maximum volume; limit listening to about 15 minutes.

- 110–120 dBA: As loud as a chainsaw, or ambulance siren nearby; can cause immediate hearing damage within seconds.

While most hearing damage these days probably comes from prolonged listening to loud sounds, sudden peak loudness can also damage your ears. Instead of time-based limits, safety guidelines for impulsive or peak sounds (like gunshots or fireworks) focus on maximum allowable peaks, since damage can occur instantaneously. Here's a rough reference based on common occupational and health standards:

- 120–125 dB SPL (peak): Upper limit for many workplace regulations; peaks above this can cause pain and immediate risk of hearing injury.

- 130 dB SPL: Pain threshold for most people; even very brief exposure can damage hair cells in the inner ear.

- 140 dB SPL: Often cited as the absolute ceiling for impulsive noise in occupational settings; single events at this level can cause permanent hearing loss.

- 150+ dB SPL: Gunfire, fireworks at close range; extremely high risk of instant, irreversible hearing damage.

Guidelines and Regulations for Safe Sound

Many countries and cities have regulations that set maximum allowable noise levels in workplaces, public spaces, and residential areas. These rules aim to protect both public health and quality of life, since prolonged exposure to high sound levels can cause hearing loss, stress, and other health issues. Workplace standards, like those from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the U.S., are designed to keep workers safe while on duty. In urban environments, local bylaws may cap noise from construction sites, nightclubs, or traffic during certain hours. While specifics vary by location, the idea is the same: keeping sound levels within safe limits reduces harm.

The Dangers Of Listening Too Loudly

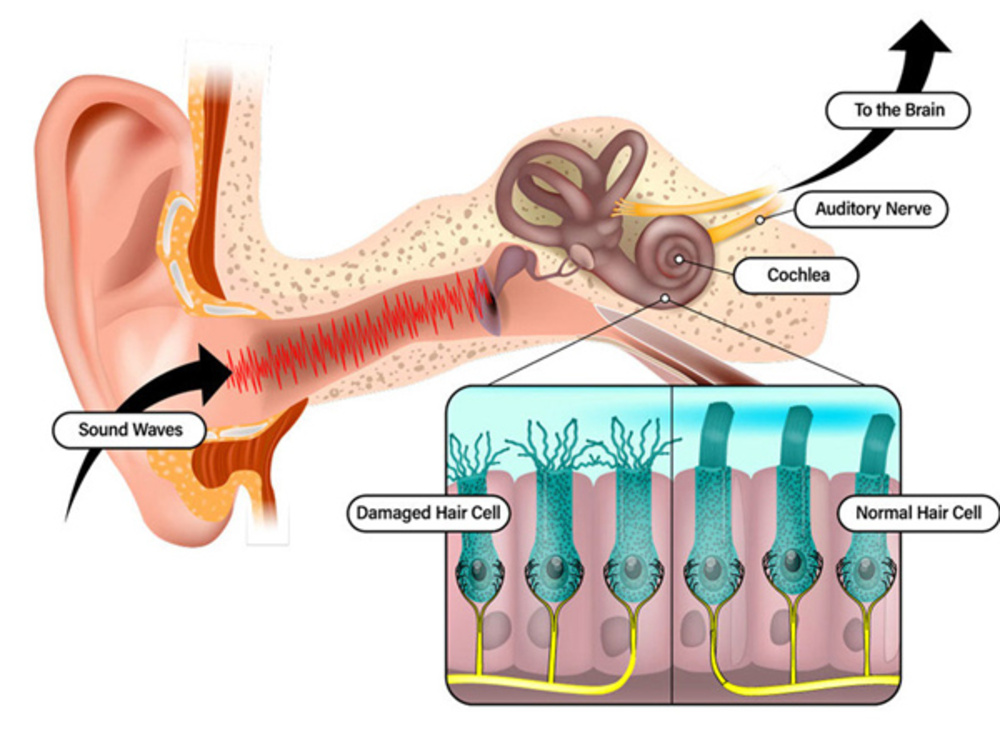

When we talk about hearing damage, we're usually talking about how intense sound waves can physically damage the tiny hair cells and nerve fibers in your inner ear that send sound signals to your brain. Loud exposure over time fatigues these cells, which you might notice as ringing ears or muffled hearing after a concert. While the ear can recover from brief, mild overstimulation, repeated or extreme exposure can permanently damage or destroy these cells (among others), leading to irreversible noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL).

Early on, this often means a gradual loss of high-frequency hearing, making it harder to hear details like birdsong or follow conversations in noisy spaces. Another common consequence is tinnitus (ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears), which can become permanent after repeated abuse. The rise of personal music devices makes it easy to deliver high sound levels directly into our ears for hours, increasing the risk of hidden hearing damage. The good news is that both NIHL and tinnitus are preventable if you limit harmful exposure and understand where 'too loud' begins.

Tips For Protecting Your Ears

Your ears are delicate instruments, but a few smart habits can dramatically reduce the risk of hearing damage. Here are some safe-listening practices to keep in mind:

- Keep the volume moderate. A simple rule is the 60/60 guideline: listen at no more than 60% of your device's maximum volume, and take breaks after 60 minutes of continuous listening. In terms of decibels, try to stay below roughly 80 dBA for routine listening. Modern smartphones often allow you to set volume limits or will alert you if you've been listening too loudly. Take those warnings seriously and dial it down.

- Limit your exposure time. Even at a safe volume, it's wise to give your ears periodic rest. Don't use headphones for hours on end without breaks. If you've been in a noisy environment (a loud bar or concert), step outside periodically to a quiet area, and give your ears time to recover afterwards. Remember, it's the combination of volume and time that matters for hearing damage.

- Check your headphones' fit. A good, snug fit keeps outside noise out and your music in, so you won't feel the need to max the volume. That's one reason we run our Frequency Response Consistency test.

- Use noise-cancelling headphones. A big reason people turn the volume up is to drown out background noise. Using active noise cancelling (ANC) headphones or well-sealed in-ear monitors can greatly reduce ambient noise, meaning you don't need your music as loud to enjoy it.

- Wear earplugs in loud environments. For concerts, clubs, festivals, or any loud events, high-fidelity earplugs are a lifesaver. They attenuate sound evenly across frequencies, so music still sounds clear but much quieter. The Etymotic ER20, for example, are usually less than $20 and come with a carrying pouch so you can always have them with you. Even foam earplugs can cut the noise by 20–30 dBA, which makes all the difference. And if you're in a situation like operating loud machinery or power tools, always use appropriate hearing protection like ear muffs.

- Maintain distance from loud sound sources. Sound intensity drops off with distance. If you're at a concert or a party with big speakers, don't stand right next to the speaker stack. Moving just a few meters back can significantly reduce the dB level hitting your ears. The same goes for home speakers: if you like to feel the thump of the bass, try to enjoy your music from across the room rather than pressing your ears against the speaker.

- Monitor your sound exposure. Consider using smartphone apps or built-in device features that measure sound levels. You could also buy a cheap decibel meter for use with speakers. A decibel meter won't be very useful with headphones, but if you're wondering how loud is too loud for headphones, check out the companion app that comes with your cans. Many smartphones and headphones can estimate the dB level you're experiencing and log how long you've been at that level. These tools can give you a sense of whether you're consistently going over safe limits. If you get a warning that you've hit 100% of your weekly safe dose, heed the warning...

- Heed the warning signs. Your body often gives feedback if you're overdoing it: ringing in your ears (even temporary tinnitus) or dulled hearing after a listening session are red flags. Don't brush these off: they are signals that the volume was too loud and stressed out your ears. If you frequently experience these symptoms or have already noticed difficulty hearing conversations, consult a hearing health professional for a check-up.

Conclusion

If you're wondering how loud is too loud for headphones and speakers, you're already asking the most important question when it comes to preserving your hearing. Loudness can definitely be thrilling, but it's also dangerous. Whether you're using headphones, speakers, or sitting front row at a concert, both the level and duration of sound exposure matter. Knowing the difference between volume and loudness, understanding safe listening limits, and recognizing the risks of both sustained noise and sudden peaks can help you enjoy your music, movies, and games without sacrificing the long-term health of your ears. There's no true single answer to the question, "how many decibels is too loud?" The figure changes with your exposure length. But 85 dBA is a good rule of thumb. As long as you stay below that figure, you're probably fine. With a few smart habits, you can turn it up when you want to, and still be listening (moderately loudly) for decades to come.