You've seen the term on forums and advertised on streaming sites, but what is lossless audio, anyway? Lossless audio means a one-to-one data-accurate representation of an original audio source. This representation is achieved without the use of destructive digital compression along the signal path and is intended to retain the sonic qualities of the original. Generally, lossless audio keeps all the particulars of the master track to sound the most 'true' to the original. The main challenges to lossless audio have to do with technological limitations along the way, such as storage space, speed of transmission, and bandwidth throttling along the signal path. That said, the easiest way to ensure lossless audio is by using a wired connection.

What Does Lossless Audio Mean?

These days, 'lossless audio' is a catch-all term used interchangeably to describe a digital file that retains all information of the original audio, or colloquially to indicate high-quality streaming and downloads. Understanding the difference between hype and genuine improvements can meaningfully impact your listening experience, data usage, storage, and choice of headphones, streaming platforms, and connectivity. Since lossless audio is purported to keep your audio pristine and is often considered a perk on streaming services, it's helpful to know whether the feature is worth the added outlay.

Out of the gate, though, lossless audio requires every piece along the signal path to be capable of reproducing the signal without discarding data, so it's more than whether your streaming platform offers lossless audio; it also relies on your connection.

Understanding Lossless Audio

Let's begin with your audio source. Lossless audio describes an information-accurate replica of an original audio master source. In digital terms, it's similar to a copy-and-paste version of the complete reference file, which means what you hear corresponds faithfully to what was copied. While the term 'lossless audio' is often used alongside other terms such as 'Hi-Res,' or as shorthand for 'high quality,' lossless audio, by definition, doesn't necessarily offer a complete metric for sound quality specifications, but rather, it measures how true to the original a copy is. As a baseline figure, though, most streaming platforms refer to any 16-bit/44.1kHz (CD quality) or better audio files as 'lossless.'

It's worth acknowledging that 'lossless' typically refers to a type of digital audio file, even though information retention as an attribute isn't exclusive to digital audio. A vinyl record, for instance, is also lossless. However, we're looking mainly at digital lossless audio as it interacts with the signal path to your ears.

Compressed and Uncompressed Files

There are two broad categories of audio files: uncompressed and compressed. Compression can mean many things depending on the context, but when discussing lossless audio, it describes how a digital audio file's data is made smaller. Uncompressed files translate to no additional space-saving measures to make the file size smaller. A lossless audio source can be as simple as a copy-and-paste of an uncompressed WAV file, but most streaming services use compressed lossless audio formats like FLAC because these create smaller files.

You can picture it as the difference between a large file and a smaller, compressed version of the same file contained in a .zip folder, which is easier to send and store but needs computer processing to 'unzip' it. In each case, they each contain the same information. Your audio player acts similarly to the processor 'unzipping' the compressed data of the compressed lossless file.

However, not all digital compression results in lossless audio files. Since lossless audio can exist in either a compressed or uncompressed form, the key requirement for lossless audio is retaining all the data. In contrast, lossy audio formats (such as MP3) are always compressed, using a more destructive type of digital compression that takes up even less storage space, streaming bandwidth, and processing power at the expense of data loss than compressed lossless files.

These lossy audio formats use more aggressive encoding to discard less perceptible information, as informed by psychoacoustics, for a kind of controlled data loss. The more aggressive the lossy compression is, the more obvious the effect is on the sound quality of the file when you listen to it, and this typically correlates with a significantly smaller audio file than the uncompressed lossless version of the file.

File Formats

There are plenty of different lossless file formats, some of which are boutique, proprietary, or rarely used. The specifications of a standard CD format (16-bit at 44.1kHz) count as uncompressed and lossless because pulse-code modulation (PCM) is uniform in its translation from an audio signal's amplitude to a digital representation at regularly sampled and quantized time intervals. The vast majority of streaming services utilize compressed FLAC for lossless audio files.

Lossless File Formats

Below is a list of some common lossless audio formats, some of which are compressed and uncompressed. While this isn't an exhaustive list, it covers the formats people tend to encounter:

FLAC and ALAC contain virtually identical data, so if you're weighing your options between one streaming platform with FLAC and Apple Music (to which ALAC is exclusive), these audio formats effectively result in the same sound quality. Any audible differences you may note come from other factors, for example, if the audio of one song received a remaster. Compressed lossless audio formats like FLAC result in larger files than lossy files, but they strike a balance by creating smaller files than uncompressed lossless audio without losing data.

Lossy File Formats

Not all lossy file formats are the same, and some lossy formats still qualify as 'Hi-Res' (more on that later), but they all use some form of destructive digital compression.

These are common lossy digital file formats:

- MP3

- M4A

- MQA (previously available on TIDAL)

- AAC (not to be confused with the Bluetooth codec)

Bit Depth and Sampling Rate

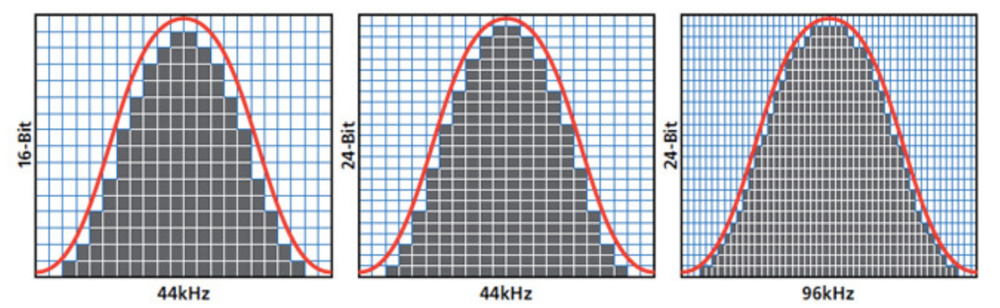

Any discussion of digital lossless audio has ties to sampling rates and bit depth, as these describe the traits of the audio file. You've probably seen 24-bit audio and 192kHz sampling rates on streaming platforms. Bit depth and sampling rates are important, as they determine how fine and granular the audio is processed as a digital format. Sampling rate and bit depth are interrelated metrics meant to balance sound quality and minimize how much space and data a file needs.

Sampling rate (sometimes called sampling frequency) measures how many instances per second of audio are captured as samples, or 'snapshots.' More samples lend more data (and take up more space); figures such as 44.1kHz represent the sample quantity.

Bit depth measures the amount of data in each sample. A higher bit depth means each sample contains more bits of data and takes up more storage. Increased density and bandwidth of data, as represented in bits, lead to greater detail, dynamic range, and lower signal-to-noise ratios.

Sampling Rates

The sampling rate measures how many instances within a standardized time interval (usually one second) an audio signal (sound waves) is converted to digital data; a higher sampling rate means more instances of a given second of audio are captured. A standard CD has 44,100 samples per second of audio. Higher sampling rates like 192kHz exist, which translates to 192,000 samples per second of audio. However, if an album was recorded digitally with a sample rate of 44.1kHz, there's no way to 'regain' those samples to make it higher than 44.1kHz.

Sampling rates alone exist outside of the lossless or lossy audio discussion because you can have lossy audio with a higher sampling rate (like 192kHz) in the form of something like an MP3 file, and you can have lossless audio (like with CDs) using lower sampling rates, such as 44.1kHz. The bigger number is 'better' if all other factors are equal, but with lossy audio, a higher figure like 192kHz essentially compensates for the negative effects of destructive digital compression on the sound quality through oversampling the original lossless file. Basically, a lossy MP3 file that has a 192kHz sample rate has taken 192,000 samples of the lossless source file, but that lossless file oftentimes was originally sourced from a 44.1kHz file (because it came from a CD) of uncompressed audio. So, despite having a higher sampling rate, a file with a 192kHz sample rate that was only ever released on a 44.1kHz sample rate CD would need to come from a different master audio source than a standard CD's files to provide more data than the CD.

Bit Depths

So, how about bit depth and 24-bit audio? Seeing a song labelled as 16-bit (or 'CD quality'), 24-bit, or (more rarely) 32-bit audio on a streaming platform is usually shorthand for lossless audio, but not always. 24-bit audio encodes more bits of information per sample than 16-bit depth audio. So, while the sampling rate determines the quantity of samples per second, bit depth describes how much data each of those thousands of samples contains. This bit depth metric informs the dynamic range of the audio and the signal-to-noise ratio. Put simply, lossless 24-bit audio has a greater potential dynamic range and lower noise relative to the audio signal than 16-bit audio.

Unlike sampling rates, the bit depth is not fixed over a time interval with most compressed, lossy audio formats like MP3s, which is why noting things like '24-bit' tends to indicate lossless audio more reliably than the sampling rate. Exceptions exist, like MQA, which is lossy but 24-bit. However, for the most part, noticing a bit depth figure listed acts as a solid clue that the audio is lossless, if you're unsure.

Lossless Audio Signal Path

To experience lossless audio without losing data along the signal path, each component in the audio chain must leave the data untouched. Broadly, this means that your worst piece of gear or technology in the signal path determines your audio signal's quality.

A lossless signal path requires a lossless audio file, a device processing the audio and sending it without altering the information, and a method of transmission (wired, Bluetooth, etc.) that maintains the data's integrity before outputting the audio from the drivers. Examples of a lossless signal chain:

- CD > CD player > wired passive headphones

- Lossless audio file > laptop > wired passive headphones

- Lossless audio file > device with USB-C audio output > USB-C wired connection to headphones like the Apple AirPods Max (USB-C version), the Beats Studio Pro Wireless, or the Sennheiser MOMENTUM 4 Wireless

- Lossless audio file > Wi-Fi-connected smart speaker or soundbar

You can't take a lossy audio file and make it lossless by using an analog wired connection. Although a wired, analog connection will preserve the analog signal that it's fed (lossy or lossless), it can't add or regain information that's already missing from the lossy digital file. Whether you'll notice an impact on the sound quality is a different question, largely answered by how sensitive your hearing is, if you've done listening training, and how much of your environment's noise masks what you hear.

Can You Listen to Lossless Audio With Bluetooth?

In general, a Bluetooth connection won't provide a completely lossless connection, but it can get close. Essentially, a lossless audio file is destructively compressed to transmit the song's data to your headphones via Bluetooth. A common higher-quality Bluetooth codec like LDAC can transmit a more complete, but lossy, version of the data than a lower-quality codec like SBC. Digital signal processors (DSP) exist on some Bluetooth headphones to predictively 'fill in' the missing data from the transmission; that's still not lossless, but it can result in convincing imitations for many. If your Bluetooth headphones have DSP, it may also make blind tests more difficult with lossy audio files versus lossless files.

For the most part, using Bluetooth with lossless audio files is more about minimizing data loss, rather than achieving a completely lossless audio signal path. Besides sample rate and bit depth, connection specs like bitrate identify how much data (measured in kilobytes or megabytes per second) is transferred from one device to the headphones via the Bluetooth codec. CDs have this too (1.4Mbps) when transferring data from the disc to the player. However, commonly available Bluetooth codecs can't consistently replicate that same CD-quality bitrate and therefore, Bluetooth codecs necessarily reduce bitrate bandwidths through (predominantly) lossy compression. For example, Apple users are constrained to the AAC codec as a best-case scenario with a lossy 320Kbps Bluetooth connection.

aptX Lossless Is Virtually Lossless Bluetooth

Some codecs get close enough that the resulting Bluetooth connection is virtually lossless, like aptX Lossless, which is capable of delivering an identical data copy of your 16-bit/44.1kHz (CD quality) lossless audio to the headphones under ideal conditions. This codec's bitrate compresses more data (about 1 to 1.2Mbps) than a CD (1.4Mbps) when sending the audio from your device to the headphones. So there's roughly 200 to 400 kilobytes unaccounted for, suggesting either very efficient lossless compression or some other proprietary workaround.

There's reason to hold this lossless audio over Bluetooth claim with some skepticism regarding the aptX Lossless. For example, consider the history of several codecs with misleading names, such as LDAC, which stands for 'Lossless Digital Audio Codec,' but isn't actually lossless. Nevertheless, aptX Lossless is your best bet for getting virtually lossless audio with Bluetooth.

Unfortunately, not all devices support aptX Lossless, and getting it running can be a hassle. This codec is one of a suite of other codecs in the aptX Adaptive collection, but not every pair of headphones with aptX Adaptive may include the Lossless codec. Plus, plenty of aptX Adaptive cans don't let you specify that you want aptX Lossless in your device's settings (even if you use Android's Developer Settings), leaving the actual audio quality ambiguous with aptX Adaptive.

To use aptX Lossless, your headphones and audio device must have a Qualcomm Snapdragon Gen 2 (or newer) chip. However, many of these Snapdragon devices aren't widely available on the North American market. Even Samsung and Apple (at the time of writing) don't support this codec.

Then again, new codecs are entering the space all the time. During this page's writing process, LHDC (the company, not the codec) announced the rollout of four compelling new codecs, including LHDC-192K and LHDC-RAW. We've not used it yet, but LHDC-RAW's advertised specs appear impressive at first glance, outdoing aptX Lossless with a stated 24-bit/96kHz transferred over a potentially blistering '<4600Kbps.'

Is Lossless Audio the Same as Hi-Res Audio?

Lossless audio isn't strictly speaking a technical term with defined specs. However, some sources utilize retroactive definitions for the purposes of delineating their products (for instance, Apple defines lossless as 16-bit/44.1kHz to 24-bit/48kHz and Lossless Hi-Res as 24-bit/192kHz). But, in truth, lossless audio doesn't adhere to specs; rather, it simply reflects whatever the definitive master audio source's fidelity is, and describes a perfectly preserved version of its information. Muddying the waters more, the definition of 'Hi-Res' remains somewhat up for debate, depending on the organization you reference. One rule of thumb to follow is that 'Hi-Res' audio files have a greater bit depth and sampling rate than CD quality audio, usually at least 24-bit depth and 96kHz sampling rate.

Generally speaking, 'Hi-Res' files qualify as lossless, but referring back to the file format (WAV or FLAC, for example) tends to indicate best whether or not a file is lossless. Audio can be lossless and not 'Hi-Res.' If you see 24-bit/96kHz, for example, it means 'Hi-Res' audio, but the type of compression applied to the file determines if it's lossless or not.

While sampling rate figures like 384kHz appear compelling, it truly depends on the type of compression used. Newer formats like MQA (which TIDAL included until July 2024) utilize advanced compression techniques that are lossy, but still result in 'Hi-Res' audio. These lossy 'Hi-Res' formats achieve their high bit depth figures by retaining the time interval and compressing noise using advanced dithering filters to a lower bit depth, and essentially filling in the difference during the processing of the compressed file before sending it to your audio output. In short, MQA is a better form of compression than MP3 encoding, but they're both still lossy, and of the two, MQA files qualify as 'Hi-Res' and MP3s don't. In contrast, FLAC files ripped from a CD are lossless but not 'Hi-Res' because CD quality is limited to 16-bit/44.1kHz.

Lossless, Hi-Res, And Bluetooth Codecs

Perhaps confusingly, 'Hi-Res' is also a moniker used for Bluetooth codecs such as LDAC, LHDC, and LC3+. For a given Bluetooth codec to qualify as 'Hi-Res,' it must conform to at least 24-bit/96kHz with a high bitrate transmission. For example, the Japan Audio Society only certifies LDAC as 'Hi-Res' when the codec is transferring at 990Kbps, but not every device is capable of that high bitrate connection. Depending on the connection you choose, such as prioritizing audio quality over connection stability, these can meet 'Hi-Res' requirements, but they're not necessarily lossless.

Most Bluetooth codecs with variable bitrates, like the Samsung Scalable Codec and aptX Adaptive suite codecs like aptX Low Latency, don't count as lossless or 'Hi-Res' because these prioritize connection stability or low latency instead of retaining all the data in the audio file.

That said, a higher bandwidth codec labelled as 'Hi-Res' loses (or destructively compresses) less data than SBC, for example. So, while marketing jargon certainly influences and confuses the appeal of 'Hi-Res' codecs, there's no disputing that a 'Hi-Res' codec, when paired with a compatible device and lossless (or 'Hi-Res') audio files, delivers more complete musical information than if you use other, more lossy Bluetooth codecs. However, these 'Hi-Res' codecs aren't lossless by the conventional understanding of the term. Even aptX Lossless becomes a lossy, but 'Hi-Res,' codec if you change the connection settings from 16-bit at 44.1kHz quality to lossy 24-bit at 96kHz quality at a relatively reduced bitrate. Still, a passive, wired connection can yield lossless and 'Hi-Res' audio without compression from Bluetooth.

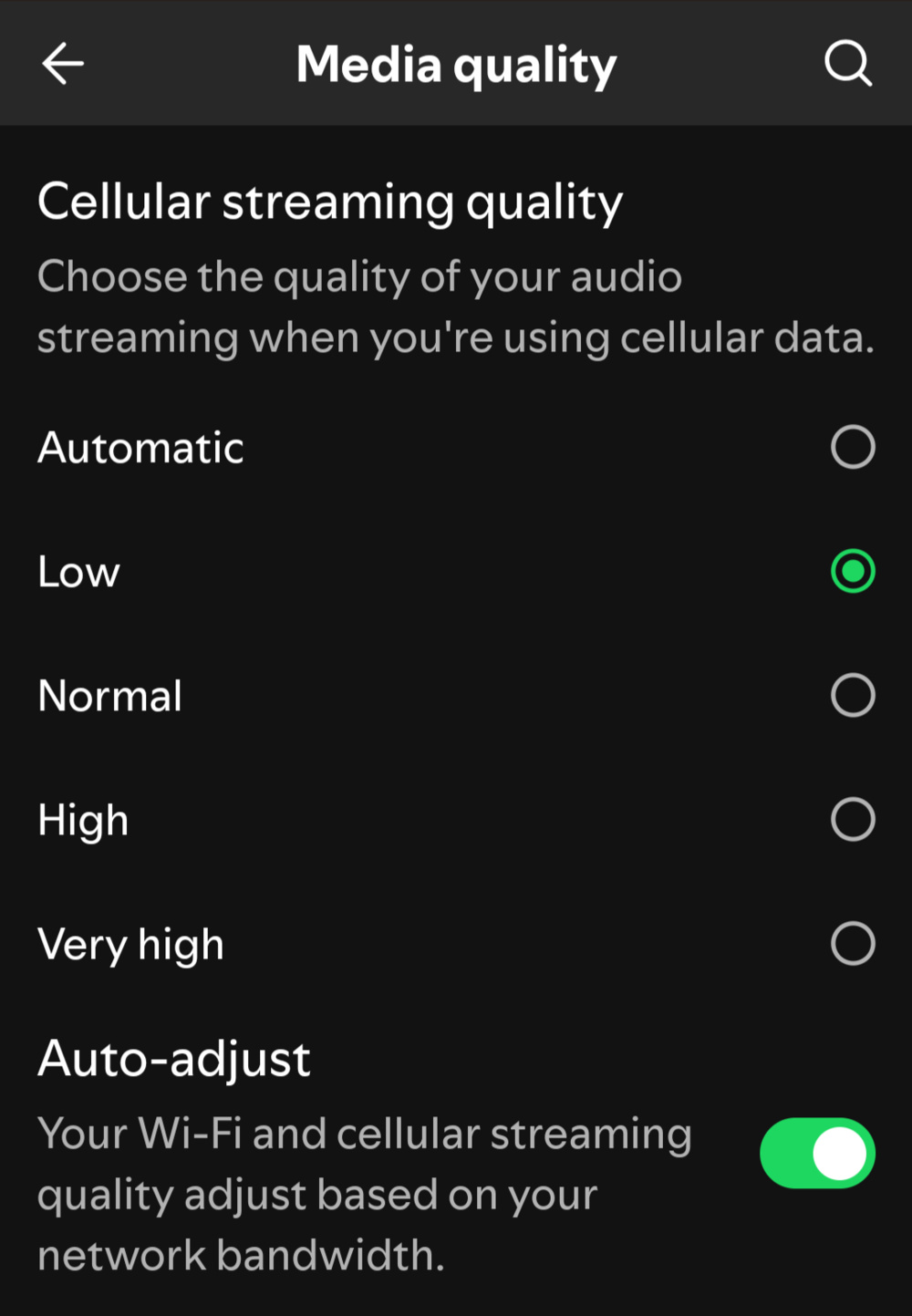

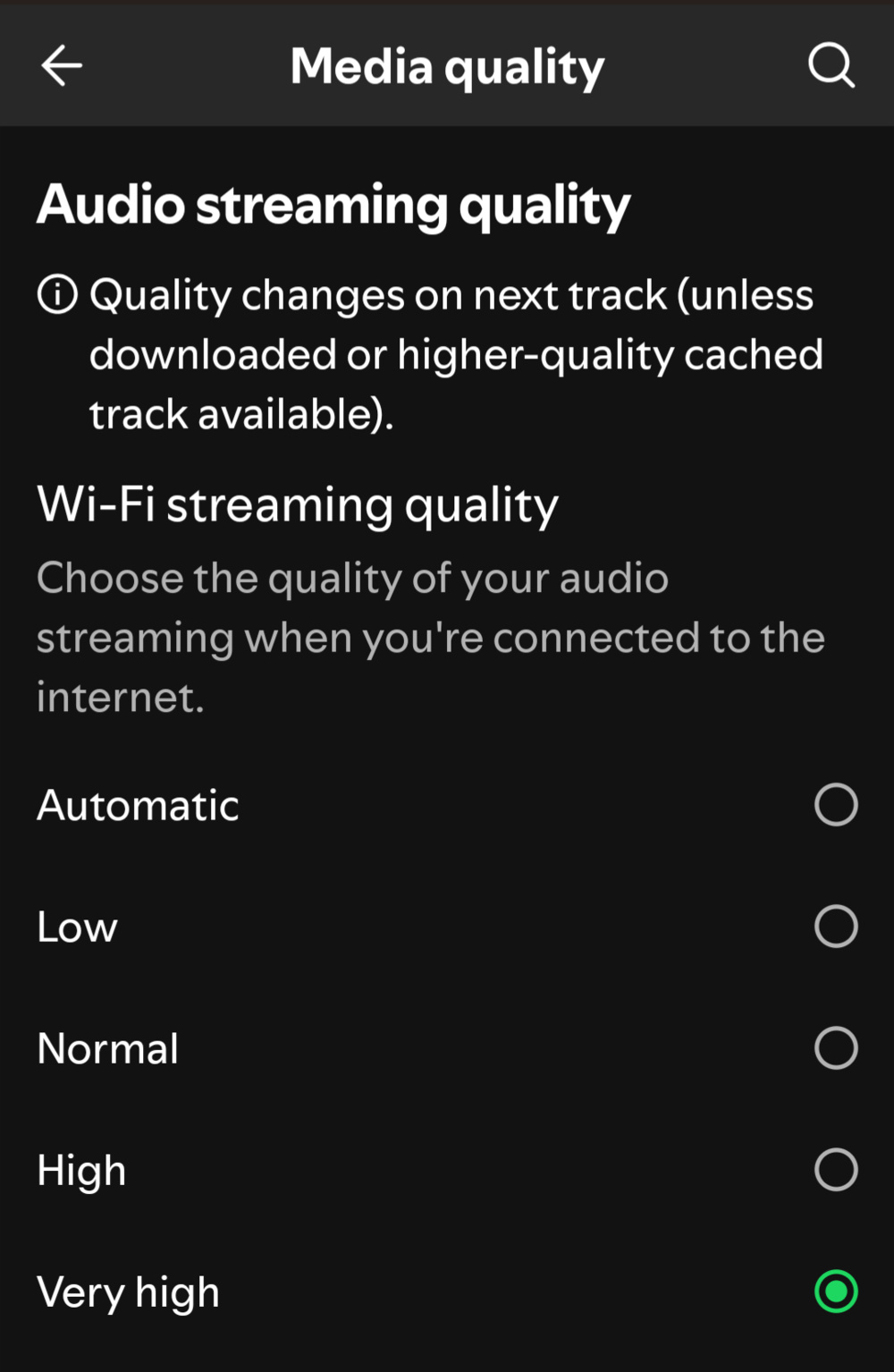

Every Bluetooth codec is unique in how it interacts with other variables in the signal chain. For example, it's not unusual for manufacturers to state that battery life is shorter when headphones connect with LDAC than with SBC. If you stream lossless audio or 'Hi-Res' audio files while connected to your phone's wireless data plan, these large files use more of your phone plan's data allotment than smaller, lossy files. If you have unlimited cell data, that's not so concerning, but it's worth keeping in mind, especially if you're not truly having a lossless audio experience over Bluetooth anyhow. Lastly, Apple products are currently incompatible with these high-bitrate Bluetooth codecs, rendering anything besides AAC and SBC extraneous.

Can You Hear a Difference?

Depending on the conditions of the listening sessions and the biology and age of the listener, some people can distinguish lossless audio from lossy audio. Lossless audio at a higher resolution than standard CD quality is also distinguishable for some people if they've done listening training. However, it's a case of diminishing returns and remains up for debate and controversial in some circles.

Most lossy audio available isn't as destructively compressed as it once was. Lossy audio's utility depends on how little data it uses during streaming and how little space it takes up in storage while balancing, more or less, the original source audio's integrity. Outside of silent listening environments, differences between a lossy and a lossless audio file are much harder to parse, too.

If your ears are sensitive to high frequencies, you may benefit from lossless audio the most, assuming the rest of your signal chain maintains the integrity of the original audio signal. But keep in mind that virtually all recorded audio and audio formats make compromises based on research and studies showing what most people do or don't detect, even if that means people with sharper hearing have to make do with the industry-standardized compromises made along the way. Consider the frequency response range of Bluetooth headphones that span, at the most, from 20Hz to 20kHz, even though research indicates select individuals can hear frequencies above 20kHz. Practically speaking, though, it requires more data processing and storage to include those ultrasonic frequencies, which remain undetectable to the majority of listeners. Similarly, CDs top out at 20kHz for the same pragmatic reasons.

A lossless file represents an accurate one-to-one replica of a given finished product, and a lossy one cuts corners to save space, but in truth, many people choose 'good enough.' Plenty of people make do with a lossy Bluetooth connection rather than a lossless wired one because the convenience and benefits of a wireless connection in some situations (such as working out at the gym) outweigh the trade-off in potentially better sound quality.

Conclusion and Takeaways

Nobody really disputes that digital lossless audio ranks as superior to lossy audio for fidelity, but whether the benefits are discernible and offset the inconvenience for all is situational. In addition, it's worth checking whether you're actually receiving lossless audio playback from your streaming platform and throughout the signal chain.

Your lossless audio experience is only as good as your weakest link in the signal chain. Essentially, if your audio file is lossless, but your device uses the SBC or AAC codec (for instance) on whichever Bluetooth headphones you own, it's not a truly 'lossless' experience due to the Bluetooth codec's lossy compression. On the other hand, if you connect a set of passive headphones into the headphone jack of a laptop and open Apple Music, Qobuz, Amazon Music Unlimited, or any other service with these files, and play a FLAC/ALAC song, then it's a lossless listening experience. Whether you can tell the difference relies on how sensitive your hearing is and the conditions under which you listen.