Wi-Fi 7 (IEEE 802.11be "Extremely High Throughput") is billed as the next major leap in wireless performance. Since the specification's publication, manufacturers have promoted promises of massive speed gains, ultra-low latency, and improved reliability. At the center of these claims sits one headline feature: Multi-Link Operation (MLO), a core capability of Wi-Fi 7 and a required feature for Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7 devices, intended to allow simultaneous use of the 2.4, 5, and 6GHz bands for faster, smoother, and more resilient connections.

The problem is that the 802.11be specification defines MLO broadly, permitting implementations that technically satisfy the requirement while delivering only limited real-world benefit. The gap between marketing and reality is substantial. In our testing of 25 Wi-Fi 7 routers, 22 implemented only the most minimal form of MLO - falling well short of the expectations set by Wi-Fi 7 branding. Three NETGEAR routers marketed as “WiFi 7” fell outside even this baseline by not being Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7 devices, and therefore were not subject to the Wi-Fi Alliance’s minimum MLO requirements.

In this article, we break down what "true" MLO entails, show how current routers fall short, and explain what to look for when evaluating Wi-Fi 7 products.

The Promise: What "True" Multi-Link Operation Should Deliver

Multi-Link Operation is not a minor add-on to Wi-Fi 7. Rather, it's the architectural shift that the entire updated standard is built around. The concept is deceptively simple: instead of treating 2.4, 5, and 6GHz as separate, mutually exclusive pipes, MLO is supposed to let a client device use multiple bands simultaneously. In a fully implemented system, those bands work together as a unified connection, dynamically balancing load, congestion, and interference. The practical benefits should be transformative. Latency-sensitive applications, such as gaming and video calls, should experience near-zero jitter because a device can instantly switch to an alternative link without interrupting the session. High-bandwidth tasks, such as 8k streaming or large file transfers, should see real speed boosts from simultaneous spectrum use. And in dense environments, a router should be able to shift traffic to a cleaner spectrum without the user ever noticing; roaming events, interference spikes, or channel contention should simply disappear behind the scenes.

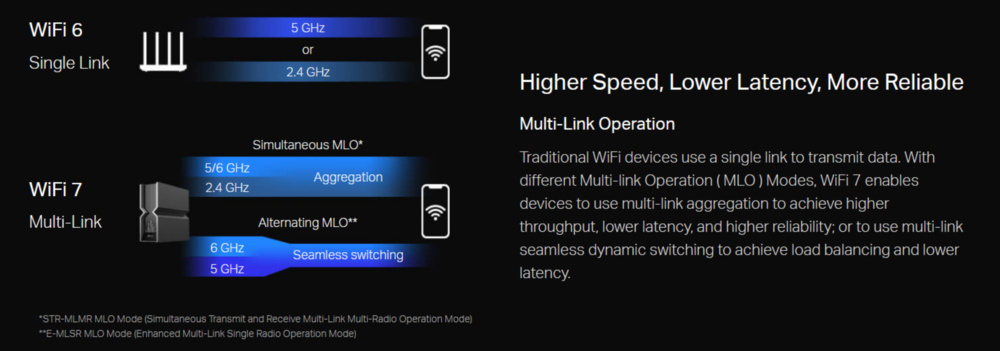

The 802.11be specification actually defines two very different modes of Multi-Link Operation: Simultaneous MLO and Alternating MLO. Simultaneous MLO is the model implied by much of today's Wi-Fi 7 marketing. Product pages often show multiple bands being used at once for aggregation and instant fallback, suggesting that a router can operate links concurrently for higher throughput and lower latency. In reality, that capability is essentially absent from current consumer hardware. What today's routers implement instead is Alternating MLO, a far more limited fallback mode in which devices can switch between bands but cannot use them simultaneously. Marketing materials make these two modes appear equivalent, even complementary, but in practice, they deliver vastly different levels of performance and user experience.

To understand why current routers fall short, we must distinguish between the two very different forms of MLO defined in the Wi-Fi 7 specification.

Simultaneous MLO (The Version Everyone Is Expecting)

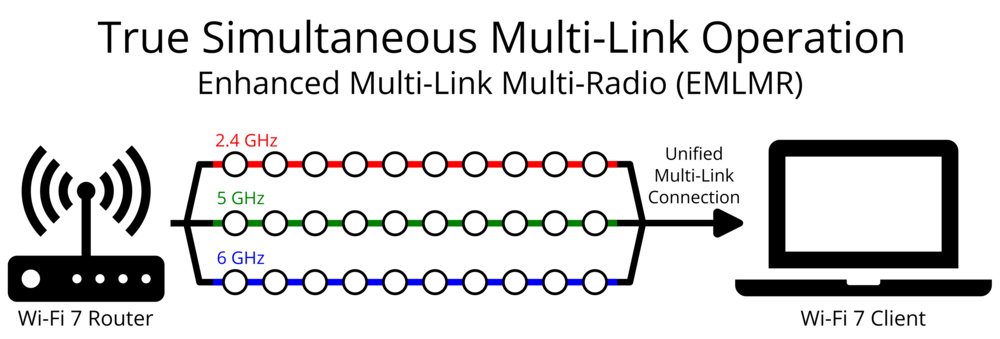

True Simultaneous MLO is supported in the Wi-Fi 7 specification through Enhanced Multi-Link Multi-Radio (EMLMR), which enables multiple bands to operate as a single unified connection. This requires precise coordination across radios, keeping them time-aligned so they can transmit and receive concurrently with microsecond-level switching across all links. To further strengthen stability and efficiency in multi-radio systems, the specification also defines capabilities such as Spectrum Resource Scheduling (SRS) and Simultaneous Transmit-and-Receive Multi-Link Multi-Radio (STR-MLMR), which help multiple radios share spectrum and operate simultaneously without creating self-interference.

Alternating MLO (The Fallback Mode Today's Routers Use)

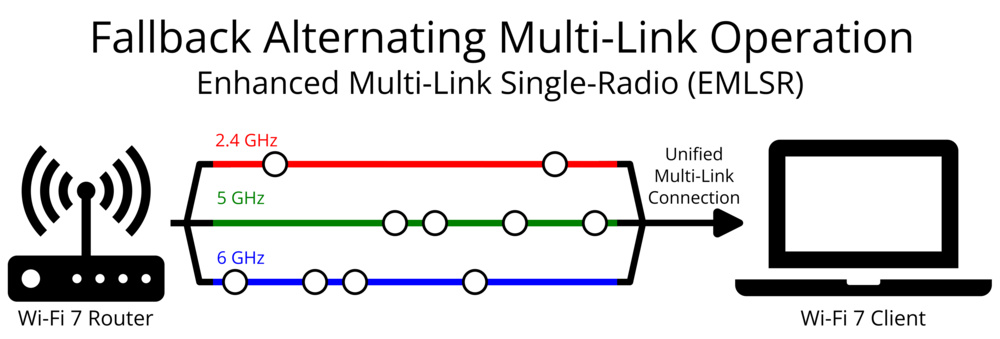

Alternating MLO, by contrast, is implemented through Enhanced Multi-Link Single-Radio (EMLSR), which is designed for hardware that cannot keep multiple radios synchronized. Instead of true concurrency, a single radio rapidly time-slices across different bands with predictable padding and transition delays. In practice, EMLSR behaves more like a refined form of band-steering than the multi-band unification the standard was envisioned to deliver. Alternating MLO is most effective when paired with features such as Aligned Target Wake Time (Aligned TWT), which is a mechanism that synchronizes power-saving intervals on the client device, and dynamic link reconfiguration, which allows an active multi-link session to be updated without disruption.

Regardless of whether a router uses Simultaneous or Alternating MLO, it will support a defined number of maximum simultaneous MLO links. In practical terms, this refers to which of its 2.4, 5, and 6GHz bands can participate in a multi-link connection at once. Naturally, the full benefits of Wi-Fi 7 are realized when a router can make use of all three simultaneously. Another capability defined in the specification is TID-to-link mapping, which enables a router and client to coordinate the assignment of different categories of traffic, such as streaming video, online gaming, or background updates, across links. When implemented, it helps make multi-link behavior more predictable, particularly for latency-sensitive applications.

The Reality: What Current Wi-Fi 7 Routers Actually Do

As noted earlier, the Wi-Fi 7 specification mandates that devices support MLO in some form, but it does not require manufacturers to implement the full set of advanced features that make MLO impactful. We encountered this gap almost immediately in our initial testing: enabling or disabling MLO on several routers produced no measurable change in throughput, latency, or connection stability compared to using 6GHz only. That outcome raised an obvious question: are today's routers actually implementing the MLO capabilities their marketing implies?

To investigate, we performed a focused protocol analysis. For each router, we first connected a Linux laptop and used "iw dev" to identify the channel on which its MLO link was operating. We then placed a MacBook into monitor (sniffer) mode and captured the router's beacon frames on that channel using Wireshark. We inspected the MLO capability and operation elements contained in those beacons to determine exactly which features the router was broadcasting at the protocol level; the features it declares to clients as available for use.

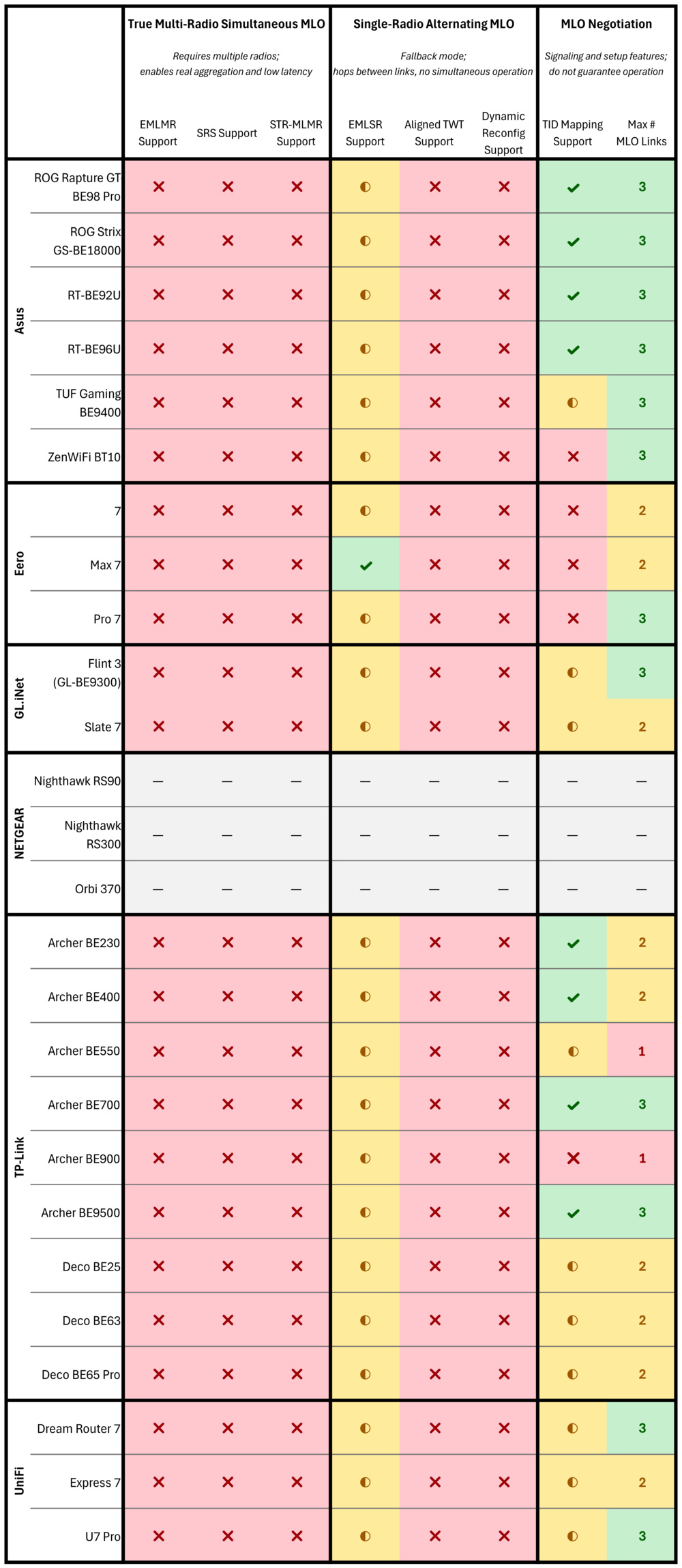

The results of our analysis are summarized in the heatmap below. Each row represents one of the routers we tested across major consumer brands, and each column corresponds to a group of MLO capabilities. These columns are organized around the three pillars of MLO operation defined in the specification:

- Features required for true multi-radio simultaneous MLO

- Features associated with the fallback single-radio alternating mode

- Negotiation mechanisms that determine how traffic is distributed across links

The color coding indicates the level to which each capability is reported in the beacon frame:

- Green for fully supported features

- Yellow for partial or limited implementations

- Red for unsupported features

- Grey where the router did not broadcast a valid Wi-Fi 7 MLO element at all

No Router Implements True Multi-Radio Simultaneous MLO

The most immediate pattern in the heatmap is the complete absence of features required for true multi-radio simultaneous MLO. None of the routers we tested support EMLMR, SRS, or STR-MLMR: the core mechanisms that allow multiple radios to operate in parallel. Even the highest-end tri-band systems, such as the nearly $1,000 Asus ZenWiFi BT10, lack the synchronization and scheduling features needed to use the 2.4, 5, and 6GHz bands concurrently as a single unified link. This gap likely reflects the limitations of current hardware, which is not yet capable of achieving the sub-microsecond timing alignment required between independent radios.

For consumers, the implication is straightforward: no current Wi-Fi 7 router delivers the form of MLO that marketing materials suggest. Without simultaneous multi-band operation, the benefits attributed to MLO simply don't materialize:

- No EMLMR means throughput gains fall far short of expectations

- No SRS prevents radios from dynamically sharing spectrum in a predictable, efficient manner

- No STR-MLMR leaves multi-radio systems unable to coordinate and avoid self-interference

In effect, the foundational features that would make MLO genuinely transformative are missing from every consumer router we tested.

Even Alternating MLO Is Incomplete

Instead of implementing true simultaneous MLO, most routers fall back to the simpler single-radio alternating mode, in which only one radio is active at a time, and the client switches between bands as needed. As shown in the heatmap, 21 of the routers we tested advertise some level of EMLSR support; however, nearly all of them report non-physical timing values, specifically 0 ms transition and padding delays. Such values are not feasible in real operation and strongly suggest placeholder or incomplete implementations. Only one product, the Eero Max 7, advertises realistic, physically plausible EMLSR timing parameters that indicate a correctly implemented alternating-mode protocol. And finally, none of the routers reported support for Aligned TWT or Dynamic Link Reconfiguration.

Because alternating MLO still serializes traffic through a single radio, it provides little of the latency benefit that MLO is marketed to deliver. And without proper timing and padding, even the theoretical advantages of EMLSR cannot materialize in practice.

Negotiation Features Reveal Additional Gaps

TID-to-Link Mapping Negotiation is somewhat more widely implemented, but still far from consistent. Only eight routers in our test set advertise full router-client negotiation capability, which allows both ends of the connection to agree on how different categories of traffic should be distributed across available links. Another nine routers advertise TID-to-Link Mapping, but without negotiation, meaning the router dictates the mapping unilaterally. In practice, this limits the network's ability to optimize latency-sensitive or high-throughput traffic and reduces the potential benefits of MLO's multi-link flexibility.

This is also where the reported "maximum number of MLO links" becomes revealing. Several routers claim support for two or even three concurrent links, but without the underlying multi-radio features or without proper negotiation, the client cannot utilize them effectively. At the opposite extreme, the flagship tri-band Asus ZenWiFi BT10 reports a maximum of one MLO link in its beacon frame. Despite having three physical radios, it does not expose even the possibility of multi-link operation to the client.

"Wifi 7" Does Not Equal "Wi-Fi 7" Does Not Equal "Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7"

Our results highlight how wireless networking terminology - and even formal certification - can obscure meaningful technical differences. In current product marketing, three similar-sounding terms are often conflated, despite having very different implications:

| "WiFi 7" | a vendor-defined marketing label with no formal standing in the Wi-Fi Alliance's certification programs |

|---|---|

| "Wi-Fi 7" | an informal reference to the IEEE 802.11be (“Extremely High Throughput”) generation of Wi-Fi technology. While “Wi-Fi” itself is a trademark of the Wi-Fi Alliance, use of this term alone does not imply certification. |

| “Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7” | a designation used exclusively on products that have passed the Wi-Fi Alliance’s official certification process and appear in its Certified Product Database. |

Of the 25 routers evaluated in this study, only three are currently Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7. Certification establishes a baseline for standards compliance and interoperability, but our results show that it is neither a guarantee of a complete MLO implementation nor a reliable predictor of real-world behavior. Notably, the only router in our testing advertise a technically coherent implementation of alternating MLO (the Eero Max 7) is not Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7.

Conclusions

Despite the marketed promise of Wi-Fi 7, our testing shows that Multi-Link Operation remains far more aspirational than real. Even among Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7 products, MLO implementations are often shallow or inconsistent. What vendors advertise as "Wi-Fi 7 performance" (or in some cases simply "WiFi 7") rarely resembles what would be possible with a fully implemented protocol. It is also worth underscoring that our analysis covers only half the ecosystem: we evaluated the router side, but true MLO also requires equally capable client devices, which today are even less mature.

Some of these shortcomings could, in theory, be addressed through future firmware updates. In practice, however, many of the missing behaviors depend on hardware capabilities that current products do not possess. This is especially true for features that require tight radio synchronization, coordinated multi-radio scheduling, and true simultaneous-link operation

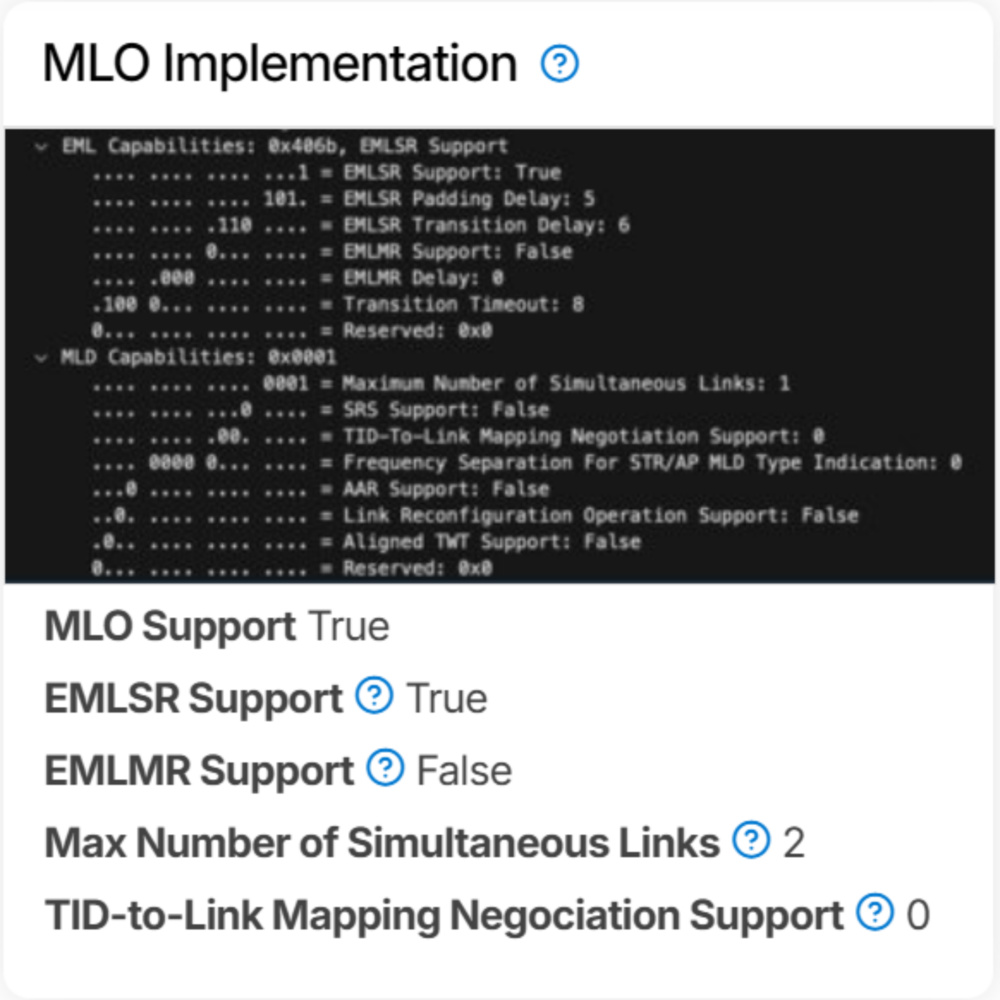

We also used what we learned in this investigation to revise our router review methodology. The new MLO Implementation box in our reviews decodes the beacon-frame fields that reveal a router’s actual MLO capabilities, rather than relying on marketing claims or certification status alone. As we continue testing Wi-Fi 7 routers, this data will allow us to track whether and when a product finally arrives with full simultaneous-MLO support.

Looking ahead, genuine progress will require manufacturers to implement the complete MLO feature set, align marketing terminology with on-air behavior, and treat Wi-Fi CERTIFIED 7 as a minimum baseline rather than a badge of advanced capability. Until that happens (and until client devices also catch up), consumers should not buy Wi-Fi 7 hardware expecting meaningful MLO benefits. The technology may eventually deliver the throughput, stability, and responsiveness promised by the standard, but in the current generation of hardware, true simultaneous Multi-Link Operation does not yet exist.